A Life in the Day

2013

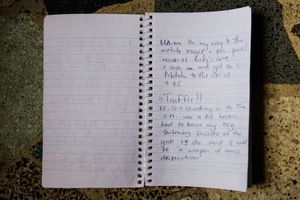

A Life In The Day_01_Production Still_Ambrose_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-2

Jean Rouch, Collaborative Film And Performed Identities - Sam Hopkins

Excerpt from Distributed: Co-producing Narratives Of Belonging in Nairobi's Eastlands. PhD thesis, UAL, Supervisors: N. Cummings, J. Bajorek

Inscrutable Ethnicity And The Methods Of Jean Rouch

The Post Election Violence in Kenya revealed ethnicity-as-political identity to be an extremely emotive identity that could manifest in an explosive manner. This emerged in the particular context produced by the politicians and political events that surrounded the elections. But what about the much harder to locate ethnicity-as-cultural identity, which existed alongside it and independently of it? How did ethnicity manifest on a lived, practiced and mundane, day-to-day basis?

It is important to explicitly state that the aim of this inquiry was not to try and explain the PEV, nor to understand how and why election violence expressed itself along ethnic lines. I was interested in revealing an ethnic identity to be a practiced and performed identity, similar to the myriad other identities I had witnessed individuals perform in my experience at Slum TV. I felt that if I could reveal ethnicity to be complex, complicated and contingent, then I could influence a national discussion that revolved around and re-iterated a series of tired, formulaic, stereotypes.(1) This was not a quest for authenticity, nor did I desire to author an authoritative account of Kenyan ethnicity. I aspired to co-author an account of ethnicity in which Kenyan individuals narrated their understanding of their lived ethnic identities.

These intentions and interests primed me for the reflexive filmmaking practice of Jean Rouch. His strategies of participation and improvisation suggest an understanding of identity as something that is constantly coming into being, which strongly resonated with my own experiences in Mathare. Rouch is well known for a filmic method where protagonists develop situations for a film through acting out scenes from their life, or from their imagination, and then narrate these scenes in the form of voice-over. This ‘method’ is not just about self-reflection on behalf of the character, but proposes an implicitly performative dimension to identity.(2) Rouch points to the idea that people are constantly engaged in a series of overlapping and intermingled performances of themselves, and that these performances are partially made from existing narratives of ethnic identity and belonging.

Rouch is a controversial figure in the history of the representation of people from Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal and West Africa. He was famously berated by Ousmane Sembène for “look(ing) at us as if we were insects” and has been accused, amongst other things, of perpetuating racist stereotypes and developing a “cinema of the exotic”.(3) But it is important to mention that Sembène makes a clear distinction between Moi un Noir (1959), which he admires, and Rouch’s more traditional ethnographic work, which he does not.

A Life In The Day_01_Production Still_Ambrose_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-2

I found Moi un Noir inspiring as frame of reference for an engaged and reflexive mode of moving-image making. In the film a group of Africans in Côte d’Ivoire play out a psychodrama about themselves, with a voiceover added by one of the main subjects and characters in the film. The subjects of the film narrate themselves as characters and sometimes contradict and criticise the unfolding narrative. But this is much more than a formal, reflexive gesture; it is a richly productive narrative device of generative and symbolic power. By handing over the expository voice-over to the actors and participants, they become a visible and audible co-author. For me this is an ethical and political gesture regarding self-representation, self-identity and co-authorship.

This intriguing and revealing filmmaking strategy of the blurring between a fictional character and a real subject is echoed in Jaguar (1967). The film features three characters acting out a fictional journey from Niger to Gold Coast (present day Ghana), the soundtrack of which is based on an improvised dialogue and account by the characters of their experiences. By making reflexivity manifest in the film itself Rouch makes it explicit to an audience that what they are watching is an artifice, not a transparent ‘document’ film. While watching the film you become aware that the off- commentary is by the people you are seeing in the film, that they are narrating what you are seeing, which is itself a reconstruction of a story they have already told. You simultaneously experience a film and a record of how that film was made.(4)

Rouch achieves a level of self-reflection with participants and within the audience. He described these films as cinéma-vérité, not “...the cinema of truth but the truth of cinema.” meaning his films are less about authentic identities than they are about the co-authorship of narrative and character in the context of the film.(5) This constant foregrounding of the context of filmmaking, and of the performative nature of filmmaking, had the further effect of reformulating a concern about the effect that a camera can have on the context that it is documenting. If it is impossible to make a camera invisible, then the inverse must be true; that a camera is a catalyst that can produce situations that would not be possible if it was not there.

A Life In The Day_01_Production Still_Lucy_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-7

This approach to making moving-image is defined by Bill Nichols as an ‘interactive’ mode, characterised by a “... situated presence and local knowledge that derives from the actual encounter of filmmaker and other”, in contrast to the ‘observational’ mode which “stresses the non-intervention of the filmmaker”.(6) As an artist interested in exploring ways to work with Kenyans to meditate on the performed nature of ethnic identity, Rouch’s interactive approach seemed to offer a number of useful reference points. His techniques of self-reflection offered a way to explore how everyday Kenyans lived and performed manifestations of ethnic identities. His use of the camera as a catalyst, and making the context of filmmaking explicit, offered a way to approach the issues of opacity I experienced in the participatory process and the moving-image content produced at Slum TV. And his acknowledgement of moving-image as the opening up of a space in which a particular identity could be performed sits well with an understanding of the innately performed nature of identities.

Developing The Interactive Method As A Collaborative Mode

“a) DAY 1 – On this day you will be asked to keep a diary describing what happens during that particular day. This could be at what time you clean your teeth in the morning, or it could describe what it is you thought about when you were having lunch. There is no right or wrong answer and it is your decision what you want to write down. I will not be with you and nothing will be filmed.”(7)

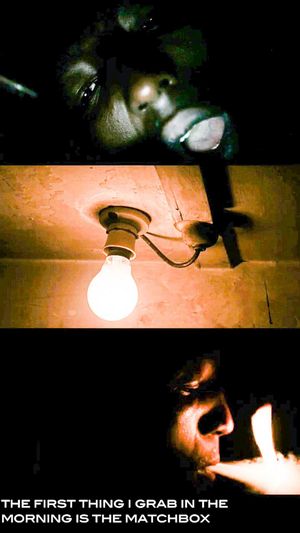

These ideas surrounding the use of an interactive method to explore the imagination and the performance of identity coalesced around the form and structure of a single day. A day offered a granular and detailed perspective on how an ethnic identity might manifest in a series of unspectacular, quotidian acts. It also provided a clear and discrete framework for participants, in which they could imagine and perform themselves, and their attendant ethnic identity, in an idealised daily routine. Using a familiar structure of ‘a day in the life’,yet staging and re-enacting it was also a wayin which to signal to an audiences that this was an imaginary, idealised day.

In developing this project I worked alongside Slum TV members as part of the production crew. Based on my experience of what I felt was an opaque participatory process in Slum TV productions I was particularly concerned with the development of an explicit process. I drafted an Information Sheet for a character and a participant in this process. The basic idea would be to ask the character/participants to write a diary for a specific day, which would then be used as the basis for a script in which they would re-enact themselves.

A Life In The Day_05_Diary_Lucy_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-4

This decision was driven by ethical concerns. I felt that by foregrounding the process by which we would make moving-image together, it would explain the process to the character/participants and offer them a means of stepping back and gain perspective on the day and the process. Furthermore, as the character/participants would not be documented during the writing of the diary, the idea was that it could be a space of freedom and fantasy: the ideal, representative day. By re-enacting this idealised ‘average day’ I hoped to open up a space of reflection and revelation for all of us about the performance, and significance, of their ethnicity in the particular contexts and situations of that imagined day.

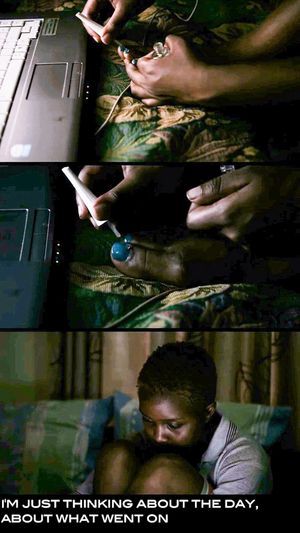

This structure was shaped by the intention to give creative agency to the character/participant at each stage in the production process. Structuring the re- enactment along the lines of a diary/script was intended to shift the emphasis onto the shooting, which could be done together, and away from the editing, which is harder to do together. Crafting a storyboard from the diary/script enabled the character/participants to make creative, montage, decisions. The last stage in this method involved a live voice-over in which the character/participants narrated the images unfolding in front of them whilst they were watching the rough cut of the material. This Rouchian technique of devolving the expository voiceover to the character/participants was intended to open up a space for reflection on the day that they had re-enacted.

Whilst my intentions and ambitions were underpinned by an ambition and desire to be transparent, pragmatic and ethical about the procedure of producing moving-image together, the result was an extremely structured and to some extent, pre-determined process. We might well ask ourselves, what kind of mode of working together is this? Does this really provide any autonomy for the character/ participants? Surely they are going through a pre-established process that they had no part in developing or shaping. To adopt the terminology of Grant Kester, is this not singularised rather than shared expression? (8)

This method and model certainly delineated the type of participation of the character/participants. But it is also true that these methods unfolded and were practiced in various and unanticipated ways. A good example of this is the way in which the diary/script phase was interpreted. Humphrey, a farmer in Western Kenya, composed a diary in which everything happens at regular time-intervals throughout the day.

A Life In The Day_01_Production Still_Lucy_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-5

The entries in Lucy’s diary are sporadic, as befits a freelance fashion designer running around the city between different clients. At first glance it would appear that Humphrey’s day is archetypal, based on what usually happens, whereas Lucy appears to write down what happens, when it happens. Indeed, the broader experience of co-producing moving-image corresponded to this apparent relationship between the diary and the day that it referred to. Lucy talked openly about her diary entries whereas with Humphrey there was no discussion about, say, whether he actually milked the cows for exactly half an hour from 7am.(9)

But we should remember that the idea behind this working method was to open up a space of fantasy in which the character/participants could perform that day as they wished, and to see if an ethnic identity played any part in that imagination. This is not about the veracity of the diaries; it is about the imagined texture of an idealised day. The stark difference between these two diary entries suggests that, from the perspective of a participatory method, the character/participants did have a certain freedom in expressing these ideals.

Why do these ideals manifest in such different ways? Is Humphrey’s day more archetypal as he is older and yearns for routine? Does Lucy celebrate the immediate and spontaneous because she is younger and urban? According to Humphrey’s diary, the whole family met for a Bible study session in the afternoon from 4pm to 6pm. When the family trudged into the room it seemed clear, from people’s body language and glances exchanged that this was neither a regular, nor popular occurrence. But just because Lucy’s re-enactment did not manifest these clear disjunctures between the actual day and the idealised day does not mean it is less fictitious. Perhaps it is rather that Lucy, being a young Nairobian, is simply more fluent in performing herself, then Humphrey is. Although this method might seem to limit the role of the participants,

if we look at how they put it to use, we see that they actively and consciously register a diverse spectrum of identity practices.

Performing Identities. Performing Ethnicity?

“Mimi ni Humphrey Sodaba. Asabuhi nasoma Biblia yangu kwa luga ya Kiswahili vizuri sana”(11) (I am Humphrey Odaba. In the morning I read my Bible in fluent Swahili)

This performative element, in which the day is a re-enacted fantasy, became explicit in the live-recorded voiceover at the final stage of the co-production. What permeates these voiceovers, is a direct description of the image on the screen, filtered by a sense of being invested in what is being described. The citation above is from the first line of Humphrey’s voiceover, over an image of him reading the bible by candlelight.

A Life In The Day_04_Production Still_Humphrey_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-13

This concern with representing his dedication to Christianity is present throughout the whole day, from this opening scene, to the way he highlights the Christian saying on his car, to the aforementioned family Bible study session in the early evening. This is not to suggest that he is not a devout Christian, but that he choses to emphasise and highlight these specific elements of the visual material in his voiceover.

Lucy is a fashion designer and this identity is constantly re-iterated in her voiceover, such as when she is getting dressed in the morning: “Here comes my favourite part of the day, dressing up. Dressing up is like a pick me up, I just feel nice and I have to make sure everything looks good ‘coz, this is what I do, I’m in the fashion business. I have to look and feel good in whatever I am wearing...”(10) The further scenes that we see during the day are visual equivalents of this: dressing up in the morning, sketching some ideas for a client, buying material at the shop and meeting the tailor in the afternoon. Lucy constantly re-iterates, both through her voiceover and the re- enacted scenes, the central importance that being a fashion designer has for her.

We never see ‘typical’ hip hop culture (performing, freestyling, cyphers etc.) in the visual material co-produced with Moroko, a rapper. But through his voiceover he infuses the everyday visual material we do see with a ‘conscious’ hip hop consciousness. Family is at the core of his identity: We see him making breakfast for his little sister, taking her to the bus and having a second breakfast with his brother. Friends are the second pillar of his identity: Hanging out with Kim, eating lunch at Kwa Maryam, refurbishing the studio, being with the warasta (Rastafarians) at Toi Market and then relaxing at Reebok Baze. He describes his friends both as “real intellects” and as the audience for his music. “as an artist usanii yangu infwatananao” (because as an artist my art follows them).(12) Moroko’s uses the voiceover to stage an entire way of living.

Humphrey, Lucy and Moroko use the staged, re-enacted day to perform identities that are significant to them, but are these related to ethnicity? Ethnicity-as- cultural identity—as something that is fluid and mutable, “a ‘thick’ ensemble of lived signs and practices”—is hard to define and identify.(13) But the performative, idealised element of these moving-image documents could evoke certain indicators, such as the particular language, food or music broadly associated with a particular ethnicity in Kenya.(14) Yet none of the re-enacted days are narrated in an ethnic vernacular nor is ‘typical’ food or music an element in the material.

A Life In The Day_04_Production Still_Moroko_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-11

These re-enactments evidence a set of references that transcend ethnic groupings, rather than being exclusive to them. The same selection of foods are seen in all of the clips, the music we hear is global pop music and the TV we see is from the United States. The elements of the morning routines that are personal to each character (Carol going for a run, Lucy painting her nails, Humphrey reading The Bible and Moroko smoking a joint) are archetypal, rather than being ethnicity-specific.

There is much more connecting the characters/participants in these performed habits and routines then there is differentiating them. This sense of shared culture is reinforced by the fact that Sheng is the common language shared by the characters/ participants. This is most explicit with Moroko. As a rapper and a wordsmith, Sheng is the tool of his trade; his voiceover is delivered in Sheng and he even highlights and translates notable words, such as “vite”, the word of a Mogoka (khat) dealer.(15) But Sheng is also palpable in more subtle ways. In her narration, Lucy often uses the construction “I usually do...” which is unusual as she is referring to one particular day.(16) But in Sheng, the suffix ‘anga’ is used to denote common actions, to usually do something, and is often used as a kind of fill in, maybe a bit like ‘yeah?’ or ‘innit’ in English slang. Lucy’s use of this construction suggests that, although the voiceover is in English, she is, to a certain extent, thinking in Sheng.

Reflecting On Ethnicity, Reflecting On Methods

Kenyan politicians routinely appeal to the uniqueness and difference of the various ethnicities in Kenya.(17) But the visual references and the layer of spoken narration in these performed re-enactments point to a set of references, and habits, that are more global and universal than they are located in an ethnicity-specific set of practices. Yet references to ethnicity are not absent in day-to-day life in Kenya. In fact, they are ubiquitous, just extremely difficult to grasp and locate beyond cliché and stereotype. It is exactly this indeterminate nature that makes this form of ethnicity so intriguing (and perhaps also possible to manipulate by politicians). I hoped that the idealised realm of the re-enacted day would give a texture and a substance to how some individuals imagined their ethnic identity. The results were moving-image documents in which any reference to an ethnic identity is almost suspiciously absent.

Did the context of producing these moving-image documents make it impossible for ethnic identities to be performed? It would be a slight paradox if a technique of co- production inspired by experimental ethnographic film practice voided the re-enactments of any mention of ethnicity.

A Life In The Day_04_Production Still_Lucy_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-12

But maybe, by foregrounding the context of producing moving-images, the individuals that I was working with were constantly reminded of the act, and fact, of being documented. And perhaps, by going on record and being viewable and accountable, the characters/participants edited out feelings of pride in, and performances of, their own ethnicity lest it be misinterpreted in the sensitive climate of the PEV. Carol, for example, spoke Gĩkũyũ and English at home with her partner, yet this does not feature in the moving-image material or the voiceover at all.

The possibility that, in performing an idealised day, the characters/participants censored out all notions of how they imagined their ethnic identities was disturbing. Because ethnic identities, in their lived, complicated, contingent and relational form, are of fundamental societal importance in Kenya.(18) Diverse, pluralised and competing notions of right and wrong, good and bad, beautiful and ugly are invaluable in producing a richer and broader epistemological and experiential realm. But as notions of Kenyan ethnicity have become so inextricably linked with Kenyan politics, and its accompanying machinations and manipulations, there is an extent to which any mention of an ethnic identity then becomes taboo. The essentialising and exclusive ethnicity-as-political identity has cannibalised ethnicity-as-cultural identity—its amorphous and ambiguous twin.

Were these issues of self-censorship compounded by the acutely reflexive nature of the co-production process? I was interested in a co-working process that devolved the authorial role to the character/participant, enabling them to stage this particular day as they wished. I was not interested in what happened but in what they wanted to appear as if it had happened. Yet, at the same time, I also aspired to a transparency regarding how this material was made, to make the context of production clear from the visual material itself. I hoped that the method of production, and the extent to which the characters/participants were involved in defining what to film would be made manifest and readable in the moving-image. Were these two intentions incompatible? Or rather, did these different aims of the work create a situation in which the characters/participants felt scrutinised by an implied but unknown audience? On the one hand the characters/participants were ascribed agency and truth claims, but on the other hand, the secret of how the moving-image was made was being shown to anyone watching the material.

A Life In The Day_01_Production Still_Humphrey_2013_(c)Hopkins/Slum TV-6

--

- See Mkenya Mzalendo, ‘Negative Stereotypes Are The Cancer Eating Kenya’, http:// www.monitor.co.ke/2015/04/09/negative- stereotypes-cancer-eating-kenya/ (March 1, 2018).

- As referenced in Chapter 1, this notion of ‘performativity’ stems from an observation of how Slum TV members were constantly acting out various identities, but it is subsequently informed by a constellation of positions that articulate the open, unmade nature of identity. See Judith Butler’s notion of gender as a verb not a noun, Paul Gilroy’s counsel that identities are inherently unstable and Stuart Hall’s idea 45 of identity as a process of formation. See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, p. 33, Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, p xi, Stuart Hall, Representation: Cultural Representations 46 and Signifying Practices, p. 47.

- For Sembène confrontation see Albert Cervoni, ‘A Historic Confrontation in 1965 between Jean Rouch and Ousmane Sembène: “You Look at Us as If We Were Insects”’ in Max Annas & Annett Busch (eds), Ousmane Sembène: Interviews (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2008) pp 3-6. For racist stereotypes see Adolfo Colombres’ critique of Moi un Noir referenced in Fadwa el Guindi’s Visual Anthropology: Essential Method and Theory (Walnut Creek: Altamira, 2004) p. 41-43.

- “...the camera gains consciousness, and the mediating work of the filmmaker is itself put on screen as a way of making a work process explicit”. See Stephen Feld (ed) Ciné-Ethnography: Jean Rouch, p. 23.

- See Jean Rouch with Enrico Fulchignoni, ‘Ciné-Anthropology’ in Stephen Feld (ed) Ciné-Ethnography: Jean Rouch, (Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, 2003) p. 176.

- Bill Nichols, Representing Reality (Indiana University Press: Bloomington, 1991) pp. 38-44.

- Information Sheet, see Appendix ii.

- Grant Kester, The One and the Many, p. 114.

- For example, the morning routine takes place at her home but Lucy asked if it would be ok 51 to shoot it at her friend’s house instead, as her parents did not support her fashion career.

- A Life in the Day_Humphrey (12.12.2012), min. 00:04.

- A Life in the Day_Lucy (11.10.2012), min. 01:16-01:40.

- A Life in the Day_Moroko (08.10.2012), min. 05:46-06:03.

- Comaroff and Comaroff, Ethnicity, Inc., p. 44.

- In this re-enacted context a cliché or stereotype about the habits of a particular group,such as the affinity of people from the Luo community for eating fish, could be appropriated as a sign of being Luo.

- A Life in the Day_Moroko (08.10.2012) min. 03:24-03:35.

- A Life in the Day_Lucy (11.10.2012) mins; 02:58, 05:27, 05:35, 05:55, 06:12, 06:31.

- “In the political sphere, leaders appeal to people of their own tribes when they want support, they also use their tribes as leverage when they bargain for positions and favors in government.” See ‘In Kenya, politics split on ethnic divide,’ October 26, 2017, http://www. dw.com/en/in-kenya-politics-split-on-ethnic- divide/a-37442394 (March 3, 2018).

- John Lonsdale frames this as a ‘moral ethnicity’: “...the common human instinct to create out of the daily habits of social intercourse and material labour a system of moral meaning and ethical reputation within a more or less imagined community... Ethnicity is always with us; it makes us moral, and thus social beings”. See John Lonsdale, ‘Moral Ethnicity and Political Tribalism,’ http://ojs.ruc.dk/index.php/ ocpa/article/view/3608/1790 (March 3, 2018).