Made in Chinafrica

2022

Have You Ever Seen Bruce Lee Before? Cosmopolitan Readings Of Chinese African Films - Jochen Becker

original publicationAfrican pastor: “Do you know Jesus?”

Chinese businessman: “Do you have a sample? I make it for you.” (from: The Qilin, 2019, R: David Lalé, Sam Hopkins)

“Chinese Africa” (1) as a bidirectional relationship between the most populous country and a huge continent has been a reality that has been experienced many times since the People’s Republic of China’s “Go Global” initiative at the turn of the millennium. It is created by state actors and companies, by workers and capital infrastructures. Since then, the Chinese government has given priority to raw material extraction around the globe in order to produce cheap products for the world market in the “factory of the world” in the Pearl River Delta and other places in China.(2) China’s “Belt and Road Initiative”, which is mythically linked to the old Silk Road changes the economic and geographical as well as the social and cultural coordinates on a broad basis.

There are numerous reports about the economic and geopolitical impact of this project initiated by China. But what is everyday life like under transcontinental conditions? How far the “Chinese-African” relationship has penetrated into this was shown by the scandal surrounding a Chinese detergent television commercial that made the rounds on the African continent as well as in the diaspora via YouTube: A woman stuffs her African machismo into the washing machine at the end to conjure up a Chinese prince of the purest race.(3)

Hallucinate the future

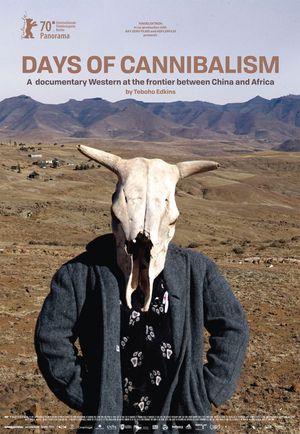

Films always have a documentary component, offer a new splintered picture of the world and also offer the chance to let things and conditions be discussed in actual as well as inauthentic speech. A growing number of artistic and documentary film works, as well as “Nollywood” productions and action blockbusters from China, are reacting to the continental shifts.(4) The film Days of Cannibalism (2020) by the Lesotho-German filmmaker Teboho Edkins, which recently premiered at the Berlin Film Festival, starts in the southern Chinese trading metropolis of Guangzhou, only to suddenly land in a barren hilly landscape with wolf masks and extensive horse races. “Chinatown, where is that?” What is your city? “I’m from Lesotho,” begins a conversation between the local customer and the somewhat awkward Chinese boss of the wholesale store. Over the course of the film, Edkins traces a deep crisis of “Chinese African” efforts in the poor South African kingdom.

“This is not a place to waste money,” says a businessman. People are here to earn and save as hard as they can so that a comfortable existence will be possible back in China. The Chinese community keeps to themselves while playing board games, cooking or karaoke: “Chain of the heart,” sings a man with tears of deprivation in his eyes. In the local bar, a black accordion player sings: “The Chinese abuse us. [...] We suffer in their factories.” In the last frame of this slowly observing film, cows are nibbling on cattle bones. Days of Cannibalism is the name of a bar in Thaba-Tseka where the filmmaker liked to stop, the end credits reveal.

The hybrid film The Qilin (2019) the British-Kenyan artist David Lalé and Sam Hopkins vibrates between silhouette-like animation and exaggerated documentary and immerses itself in the hustle and bustle of the southern Chinese trading and port city Guangzhou one. The one based on a fable. The film, named between an African giraffe and a Chinese dragon, leads through endless goods presentations, logistics hubs and container ports, interrupted by a chorus of interviews from the African traders, anonymized with black overpainting. “We are blessed with this entrepreneurial spirit. We have the ability to hallucinate the future. “We see something that others don’t see,” fantasizes an African trader. The awakening experience of African Pentecostal churches, which want to reconcile belief in God with economic success, meets Confucian neoliberalism in China.

Flying legends

African kids in “kimonos” recreate Chinese cinema scenes on sandy ground in Gabon for their black and white home video. Luc Bendza saw so many kung fu films in his youth in Gabon that he wanted to leave the country when he was 14. “I’m going to China to fly,” he says, laughing. Because he expected there to be floating people with swords and pigtails on horses, just like he had seen in the movies. When he visited the Beijing Film Studio, he realized that five people on a rope(5) were jerkily pulling the kung fu actors into the air to make them fly: “Of course I was disappointed. I learned that different criteria applied in the cinema.”

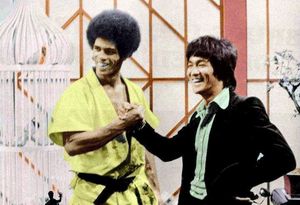

The filmmaker Samantha Biffot, who commutes between Paris, South Korea and Libreville, accompanies her busy protagonist for five years in her documentary The African Who Wanted to Fly, completed in 2016. In Chinese competition stadiums, Luc demonstrated his “African drunken man style”, combined with reenactments, Fight scenes and slapstick. In 1994, representing Gabon, he won first place in the global Wushu competition: proud and lonely at the same time, because no compatriot could cheer him on. In the 2000s, a former Bruce Lee producer approached Luc Bendza - he can finally star in Chinese martial arts films such as the biopic The Legend of Bruce Lee.(6) Now he meets at the Shaolin Temple in Henan province on black muscular upper bodies and white Asian martial arts pants in a dance-like choreography. The Kung Fu pilgrims come from Congo, Senegal, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Benin: China and Africa have now moved closer.

Kolik Film_Sonderheft_Becker_2020_The Qilin_(2019)_Still_(c)Lale/Hopkins

Luc worked in the Wushu department(7) at the sports university in Beijing for 20 years: “For me, it was a big deal to introduce young Chinese people to their own culture.” But the students' parents distrusted him. Luc's Chinese wife talks about everyday Chinese racism and how her parents would never have allowed her to marry a stranger.

They speak French to their “Chinese African” child. “What do the Chinese know about Africa? [...] They see it like the Europeans: poverty, constant wars, nothing positive, just animals and thieves and diseases,” says the African comedian Francis Tchiégue. “Our image still needs to be rebuilt.” Luc is now training “future champions” in Gabon. But back home in Libreville, many people find it too Chinese. Relatives there are amazed at how backward China appears in the films: “China seemed extremely traditional. Films are always set in villages, and I didn't see China as a developed country. You never saw anyone driving a car or sitting on an airplane. I don't even know how to get there.” So while Luc wanted to discover the Wushu tradition that dates back 5,000 years and only found it in sports courses at his university in Beijing, his African relatives are amazed at its antiquity China, which doesn't correspond to their modern life in Gabon at all. The power of cinema brings the continents together, but sometimes also leads them astray.

Black Maoism

The concrete and everyday “Chinese African” encounters are preceded by individual as well as mass cultural experiences, mostly conveyed through popular arts. Vijay Prashad, director of the Tricontinental Institute for Social Research, describes the connections between Bruce Lee and black emancipation in his 2001 book Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting(8). Even as a child in Calcutta, Bruce Lee promised Prashad liberation from an oppression to which one was defenseless. The author, who commutes between Delhi, Beirut and Northampton, suggests a cosmopolitan reading of Asian martial arts: “In the end, in the world of Kung Fu, non-whites dream of a bare-fisted revolution against the heavily armed fortress of white supremacy.” When Lee conquered screens around the globe with Enter the Dragon (9) in 1973, the Vietnam War had reached its decisive phase: “Bruce did this without weapons, with bare feet and fists, dressed in black, as is associated with the North Vietnamese army ." Two years later, "Bruce Lee would give us the perfect allegory of both Asian American radicalism and the Vietnam War with The Way of the Dragon," Prashad writes of his cinema-literate youth. “The liberation was not limited to the silver screen or the silver screen.” In the fight against the ultra-right martial arts actor Chuck Norris, “Bruce takes his time, but as he destroys him, the fight in the Roman Colosseum becomes a fight between the Western and Chinese civilization”. The setting combines the imperial ruins of Europe with colonial oppression in Hong Kong or Vietnam. Lee, who also serves as director here, uses Sergio Leone and his crazy zooms, close-ups and editing techniques. Even the Song of Death is played when Chuck Noris appears for the first time.

Kolik Film_Sonderheft_Becker_2020_Enter the Dragon_(1973)_Still_(c)Clouse

Resistant Kung Fu schools opened in the US ghettos, and the Black Panthers learned to fight alongside Chinese communism: “Karate requires no fancy equipment, just a small room, bare feet and bare hands.” China's anti-racist Position promoted “black Maoism”: In the Cold War it is less Moscow than Beijing, which, as a pioneer of the non-aligned movement, supports Africa's decolonization economically, medically and militarily.

“One could say that martial arts traditions such as Kung Fu [...] involved Kalarippayattu from Kerala, Capoeira Angola from Brazil and the various martial arts of Africa in complex ways. Kung fu is not far from Africa and not far from the favelas of Brazil." In Enter the Dragon, the African-American fighter (Jim Kelly) is heard saying, looking at the massive boat slum in Hong Kong Bay, that "Ghettos “the same everywhere in the world”. Prashad offers an anti-essentialist and “polycultural” reading of kung fu beyond simple identity politics. This means thinking and acting in an international of resistance, because today's "Afro-Asian and polycultural struggles indeed enable us to redeem a past that historians have carved up along ethnic lines." Across continents, this work of remembrance is shaped and driven by (pop) cultural interweavings.

A Chinese Rambo saves Africa

Wuxia films have been produced in Hong Kong since the 1920s. Popular martial arts fiction peaked in the 1960s to 1980s and gained widespread international attention beginning in the 1970s. In the wake of Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), the tradition of wuxia films was revived - now in China.(10) Kung Fu now increasingly serves as a technique to secure power and a state Chinese instrument of power, for which the most recent Wolf Warrior film is particularly popular. Series by and with Wu Jing is available. The Beijing-born Chinese martial arts star and Hong Kong resident studied at the Beijing Sport University at the age of six (maybe even with Luc Bendza?). His blockbuster Wolf Warrior 2 (2017) is considered the most successful Chinese film ever released. Leng Feng (Wu Jing), a soldier from the special unit “Wolf Warriors”, will not only stop the bulldozer-assisted eviction of the relatives when presenting the urn of a fallen man, but will also kill the building contractor. The hero is still on the side of the oppressed, but there is no longer much of the elegance of Bruce Lee. This also seems to be more of a relief scene, probably to put the constantly demonstrated patriotic commitment to the Chinese nation into perspective. Here, the patterns of military and weapons parade pathos perfected by Hollywood, such as in Rambo, are copied almost identically.

Kolik Film_Sonderheft_Becker_2020_Wolf-Warriors_(2017)_Poster_(c)Wu Jing

Three years later he landed in an East African Francophone port city that is reminiscent of Djibouti. In addition to European and US troops, the People's Republic of China has now also secured its first military overseas port, also because the railway line from Ethiopia's capital Addis Ababa, built by Chinese state-owned companies, ends there.(11) China is copying the military-imperial economic policy of the West, and Like in a picture book, Wolf Warrior 2 declines the new politics almost completely.

The initially sunny, informal African backdrop shows cracks when doctors remove Ebola infected people from the streets. A sudden invasion of rebels and mercenaries turns the place into a blood-soaked “killing field”. Chinese territories in particular offer protection: a shop, a hospital or a factory, the naval convoy or the embassy. A diplomat in a suit heroically shouts: “Weapons down! Step away! We are Chinese! China and Africa are friends!” What initially sounds incredibly silly in the face of a motley crew of killers, runs through the entire film – not without a real background: If anyone else can help here, it is the People’s Republic, also because they can would rather not mess with this potential alliance partner.

Since the Tricontinental Bandung Conference in 1955, the People's Republic has promoted and demanded a “policy of non-intervention”. But Wolf Warrior 2 repeatedly calls this into question when the ambassador demands direct military intervention to save other compatriots. This is stoically refused - "I cannot send troops into the war zone without UN permission" - until the commander sends out a barrage of rockets in response to a massacre broadcast on WeChat video.

An evacuation convoy moves to the port and crosses dark streets littered with looting and corpses: “Twelve years of hard work... One war and it's all over.” That's just how it is in Africa, always just dead - if China didn't intervene. A “Doctor Without Borders” knows her stuff, played by the international Celina Jade. She is a Chinese-American actress, model, singer/songwriter and martial artist based in Hong Kong.(12) Meanwhile, in a Chinese factory (13) the selection of the Chinese factory boss begins: “All Africans please stand on this side. We only take Chinese people, the management comes first.” Here, as on the construction site, anti-capitalist resentment is flaring up, embodied by a multitude of workers who are solidarity with collegiality, friendship and love and who are successfully revolting against it.

China's once emancipatory efforts in the 1960s and 1970s have given way to a paternalistic world-savior gesture that knows and can do everything better, otherwise the African continent would sink into rubble and ash. The image politics reminds us of the “natural wildness” of Africa when a lonely zebra is torn apart by lions on the side of the road. The film describes China's neo-imperial interests in and on the African continent in great detail. A cinema poster purports to show Leng Feng giving the middle finger with the slogan "Anyone who insults China, no matter how far away, must be exterminated." The departure from the anti-colonial spirit of Bruce Lee could not be formulated more clearly.

Kolik Film_Sonderheft_Becker_2020_Head Gone_(2014)_Poster_(c)Fasisi.jpg

Daily Madness

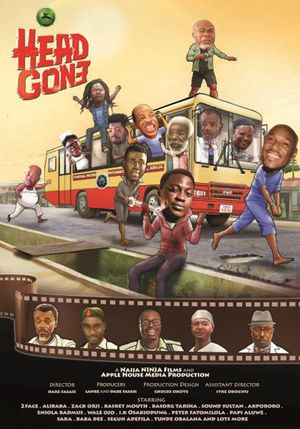

“Chinese Africa” and Kung Fu are also topics in the digital genre “Nollywood”, i.e. the everyday seismographic video film scene from Nigeria, which is already in third place in the world market in terms of production output after Hollywood and Bollywood. “Nollywood” was (and still is) distributed on roadside CDs, but also early on via streaming portals. The Nigeria premiere (14) of Head Gone by Nigerian-Swedish filmmaker Dare Fasisi took place at the end of 2014 in what was then the first and only multiplex cinema in Lagos. With its elaborate camera perspectives, animated sequences and split screens in the opening credits, the work is still considered a successful “Nollywood” film to this day. Towards the end, however, the film gets a little lost in its multiple narrative strands.

In Head Gone, stars of the “Nollywood” scene (15) go on a trip through the Nigerian madness – “Madness” is a phrase that quickly comes off the lips here. The film repeatedly shows posers in fantasy uniforms, presumptions of office by various “authorities” and self-proclaimed “area boys” full of arbitrariness, corruption and machismo. Such attacks “during this time of ritual killing, Boko Haram and kidnappings” are often consequences of the civil war situation in Nigeria that lasted until 1999, and has now been extended by acts of terrorism by and against Islamist fighters.

The film weaves individual fates as flashbacks and shows a specific fish socio-political medical history on. So there is a former general continues to suffer from post-traumatic stress in the Biafran War, which he fought through the two homemade tin cans glass tracked. At a dinner and flirting party break from supervision, the “crazy people” escape from the bus – many of the pictures remind you certainly not by chance to Miloš Formans political “crazy film” One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975). To not with one standing there empty transport, they collect both supervisors new ones over the course of the trip “Insane” appears while the patients are in the normal lives occur. Attempts to differentiate between “healthy” and “sick” regularly fail. “Catch the crazy people, they can be anywhere,” the government shouts on the radio and randomly picks up people with behavioral problems. A student activist (the performing activist Segun Adefila is struggling to survive in the Bariga slum district) wants to call a demo and is arrested.(16)

Aside from the normal insanity, a series of sequences shed glaring light on the “Chinese African” conditions in Nigeria. As a self-authorized chauffeur, an escapee takes two Chinese entrepreneurs with him: "Are you the company's driver?" the two ask cautiously, but instead of being taken to the headquarters, they are thrown around in an adventurous way. The newcomer to Africa is surprised while his colleague, who wants to appear sophisticated, tries to make it clear to him that this is the local driving style: “Don’t worry, don’t worry.”(17)

Kolik Film_Sonderheft_Becker_2020_Cover_The African Who wanted to Fly_(c)Neon Rouge

The supposed chauffeur takes them to an informal settlement, accompanied by shouts of “Ibo, Ibo” that the “whites” like to hear. With their khaki-colored tropical dress or the old-fashioned suit, they seem pretty lost here. “You think you're Bruce Lee?” they shout, as kung fu films are considered an accurate reference system for assessing these strangers. “Have you ever seen Bruce Lee?” the person being addressed adjusts his anachronistically cool sunglasses. In general, he suddenly looks different in his weird suit and wide tie as if it came from a film from the 1970s. "Wow. This is real Bruce Lee,” is the acknowledgment of the “boys from the hood” as the fighter knocks two people to the ground. Soon they are fraternizing and dancing exuberantly through the streets between kung fu moves and Afrobeat.

Right at the beginning of the film, the logo of the production company “Naija Ninja Films” appears, which also acts as a music and clothing label for Baba Dee and his brother Sound Sultan. “Naija” is the pet form of Nigeria, and “ninja” is a “specially trained fighter from pre-industrial Japan,” according to Wikipedia.18 Dare Fasisi demonstrates “Chinese African” reality in everyday scenes between Borat-like “cultural learning” and a meta-reference system trained in pop culture . “Chinese Africa” is a process embedded in a radical neo-liberal market process and at the same time in search of a liberating decoloniality.

--

- The China Africa research and exhibition project. under construction was developed by Jochen Becker (metroZones) with Daniel Kötter, the working groups were accompanied by Huang Xiaopeng (Guangzhou), Michael MacGarry (Johannesburg), Patrick Mudekereza (Lubumbashi) and Folakunle Oshun (Lagos). As part of the China Africa exhibitions. under construction (Graz 2016, Leipzig 2017, Nuremberg 2019) and China Africa. blackout (Shenzhen 2017/18) as well as the performative setting of China Africa. mobile (Weimar 2017) we showed various artistic, documentary and fictional video films, each of which took a specific look at a tricontinental phenomenon. See www.chin-africa.org.

- The iPhone has become a product of “Chin Africa”: The exploitation of the Congolese coltan and copper mines for the millions of smartphones produced by a Taiwanese group of companies in Shenzhen by a US company shows how this company globalized and linked via container ships, airlines, data lines and standards Capitalism interlocks across continents so that the devices are distributed all over the world, including the African markets, and are ultimately recycled as electronic waste in Lagos, Accra or Hong Kong for residual raw materials. Daniel Kötter's video China Africa, partly shot by actors. mobile (2017) moves, among other things, in Congolese mines and Chinese factories. His essay Yu Gong, written in 2019, is discussed in more detail elsewhere in the issue.

- As if that weren't enough, the spot is a reversal of an Italian advertisement, copied right down to the background music, in which a white man enters and a black superman comes out: Coloreria Italiana - Colored is better.

- Even the important contemporary director Jia Zhangke is said to have a project planned for this.

- These martial arts films are called “Wire-Fu” because of the special effects.

- The 50-episode television series was produced by Chinese state broadcaster CCTV in 2008. Luc took over here the role of the black boxer Jesse Glover, who was Bruce Lee's first student in the United States in 1959 was trained.

- This martial art form is now primarily aimed at exhibitions and competitions and includes acrobatic jumps and effects.

- Vijay Prashad, Everybody Was Kung Fu Fighting. Afro-Asian Connections and the Myth of Cultural Purity, Beacon Press 2001.

- The complete and feature-rich Bruce Lee collection is currently being released in the excellent Criterion Collection. His Greatest Hits with 7 DVDs.

- These include international successes such as Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004) and Reign of Assassins (2010).

- However, the scenes were primarily filmed in the townships of Soweto and Alexandra near Johannesburg later in the post-industrial desert of Hebei Province.

- Her father Roy Horan appeared in front of the camera in 1977's A Dragon Story and 1981's Game of Death II with Bruce Lee.

- The rusty industrial area is now being destroyed. The former ironworks in Zhaochuan served as the filming location Town in the Xuanhua District, where high-tech development zones are being created in real life - as before in the special economic zones around the Pearl River Delta, which in turn are considered models for outsourced industrial zones in Zambia, Nigeria or Ethiopia. In this respect, the martially presented end of the African “Rust Belt” is only consistent and is reminiscent of scenarios in RoboCop or Transformers, where industrial areas in Detroit or California are dismantled to fit the screen

- The world premiere organized by AfricAvenir previously took place in Berlin.

- Among others with 2Face (Tuface) Idibia, Alibaba, Zack Orji, IK Osakioduwa, Basketmouth, Papi Luwe, Peter Fatomilola,Eniola Badmus, Basong Tariha, Sound Sultan, Akpororo, Wale Ojo, Saka, Baba Dee, Segun Adefila and Tunde Obalana

- The Soviet Union also locked up dissidents in psychiatric hospitals.

- “[Speaking another language]” appears regularly in the version found on YouTube when in Nigerian