Not in the Title

2012

Not in The Title_02_Installation Shot_Detail_2012_(c)Hopkins-5

Rewind To The Beginning | A Prologue | Reflecting (artist Statement Written In 2011) - Sam Hopkins

When I was asked, sometime in 2010, by Ulf Vierke and Nadine Siegert if I was interested in making an artwork based on the archive at Iwalewa-Haus my initial idea was to explore and investigate the idea of authenticity in relation to cultural production. What happens to an object, an artefact, a work of art when it is transported from its original context to new one? From Africa to Europe, from South to North, from site of production to site of display? And not just a site of display, the artefacts and works of art in the Iwalewa-Haus exist in the context of a museum and an archive, both of which entail a certain set of power relations. How would these recalibrate the object/work of art in question?

With these ideas in mind I went to Bayreuth for a research trip. You could say I was conscious of the shape of the box but I did not know what would be inside. I had a vague idea that the collection at Iwalewa consisted of predominantly traditional artefacts, but beyond that I was not really sure what to expect. When I arrived Ulf explained to me that there were actually various collections, ranging from Contemporary Art, to traditional artefacts to textiles and music. They were all upstairs and I should go and explore myself. I decided to start from the beginning. I walked up the creaking wooden staircase to the top floor of Iwalewa-Haus, went to the end of the narrow corridor to the end room, then through the end room to the very last room.

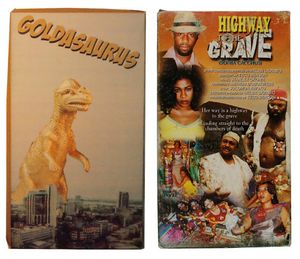

When I opened the door and turned to look around I was confronted by an Ikea's bookshelf worth of VHS tapes. I have to admit I have a slight nostalgia for VHS. Even although we have just entered the digital revolution, it is so immersive that the world of analogue video already seems to belong to a very hazy past. I picked up a tape at random, and had that immediately recognizable feeling of the video not weighing quite as much as you expect it to. I read the title; 'Highway to the Grave', the caption; "Her way is a highway to the grave, Leading straight to the chambers of death". In the corner of the small room was a TV with a video player connected; an apt addition to the archive. I inserted the tape, pressed play … and it worked.

What followed was my first real experience of a Nollywood horror film. I think my overriding impression was of a film that seemed to elude both understanding and judgement. It was scary and funny, boring and intriguing, simplistic and nuanced. The special effects were lo-fi but highly imaginative, the roles were over-acted but often understated. Part of me wanted to reject the film as a rushed script with poor production values, but another part of me was totally captivated, almost literally.

Not in The Title_02_Installation Shot_Detail_2012_(c)Hopkins-5

Sometimes films affect me with an almost narcotic intensity; it's less a willing suspension of disbelief and more an utter absence of doubt, a temporary state of acute amnesia where I forget that I am outside the film. Almost like that sci-fi scene I felt that I was being hauled head first into the TV set, physically transported to a strangely coherent world of Nigerian horror.

When I got back from my trip I had another look at the bookshelf which revealed that the majority of the videos in this collection were horror films, featuring zombies, devils, priests and businessmen. 'Fatal Desire', 'Holy Crime', 'End of the Wicked', “Gods Incarnate'; this film was not a one-off, but part of a whole genre. I was totally seduced, and performed a somewhat cursory exploration of the remaining collections at Iwalewa. Not only was the video material exciting but also the fact that the collection existed at all intrigued me. How had a collection of predominantly Nigerian horror films, mainly from the 1990s, ended up in Iwalewa-Haus? Asking around a little revealed the source; a previous director of the Iwalewa-Haus, Tobias Wendl, had a passion for African Horror and had instigated this collection. But how had this selection been made? There are approximately 175 videos in this selection, but Nollywood is famous for producing thousands and thousands of movies every year. In fact, one of the pioneer directors Chico Ejiro, also known as 'Mr. Prolific' is said to have produced 80 films in his first year alone.

Any collection is by its nature exclusive, and that exclusion is based on criteria. But beyond the predominance of the horror genre and the timeframe I could not discern what the criteria for this selection might have been. Given the quantities of films produced in any one year, there must have been thousands that were excluded. Nevertheless these films in Iwalewa-Haus were collected, and, critically, were digitised and stored on a secure server. Hypothetically speaking, in 100 years time, when all the original VHS tapes in Nigeria had decayed it would be these films in Iwalewa that would stand for the cultural production of their time. These videos had been canonised, and arguably, fetishised. Nevertheless, from what I could see, the selection had been basically subjective and I felt that this subjectivity seemed to clash with their status of authenticity.

So these twin issues became my starting points. Enigmatic films that I did not really feel equipped to decipher and a collection based on mysterious criteria that I somehow did not really trust. I felt less like an artist and more like a detective. But I was not sure that I really wanted to solve the case.

Not in The Title_01_Production Image_2012_(c)Hopkins-1

I liked the mystery surrounding these films, squirreled away in the antipodes of the building. It made them feel special. It made me feel special, but also suspicious. And suspicion begets a heightened awareness; a critical view that is sensitive to details, a sensory state of perception that is reactive; an imagination that is fecund.

It reminded me of one of my favourite authors, Jorge Luis Borges, who writes metaphysical parables, sometimes no more than 2 pages long, in which he manages to transport the reader to familiar but alternative realities. One of the ways he achieves this is by spinning a web of references to other texts, but you soon realise that some of these texts are real and some are apocryphal. The result is that you read everything in a kind of limbo of authenticity; believing nothing entirely but everything a little. The state of mind of that this way of reading engenders is both one of constant doubt and one of wonder. When I read these stories I feel actively engaged in the process of making meaning and as a result my imagination experiences an almost psychedelic stimulation.

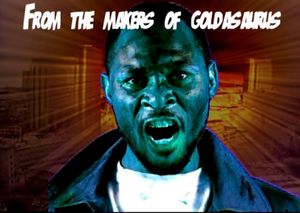

I wondered if I could take the Borges strategy of mixing real and apocryphal references and apply it to the Nollywood material? How could I intervene in what I felt was an illusion of authenticity? What would happen if I digitally manipulated the material to insert new characters? Could I destabilize the idea that these films were somehow pure and authentic? And if I mixed this generated material with original material what would that do to the viewers’ experience? Could this create a heightened sense of awareness in the viewer that I experienced as a reader? Would it enable them to interrogate the material in a way that I could not, watching all the original material? Furthermore, could this openly-stated intention of mixing 'real' and 'fake' material start to question the nature and selection of the original material? These were the questions and intentions that my ideas began to orbit around.

Returning to Bayreuth for the residency several months later the idea of creating a kind of visual equivalent of a Borges fiction was still my main concern. Initially my plan was to use a green screen (footnote) to insert new characters into the original material. I had figured out a way of using a projector so that these new actors could interact 'live', albeit simplistically, with the original characters in the films. The idea was to screen the manipulated material together with the original material. In the installation setup I would signal that some of the material had been 'faked', but not indicate which parts; the idea being to inculcate a sense of suspicion in the viewer and trigger a kind of 'Borgesian' awareness that I discussed earlier.

Not in The Title_01_Production Image_2012_(c)Hopkins-2

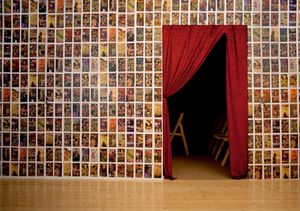

But, as I started to work on the material and in the space, rather than just working visually, I began to think of creating an immersive environment which viewers could experience and walk through. I wanted to explore the sensation that I had first had when seeing the material; the idea of piecing together a story, of being a detective, of wondering how all the pieces fit together. To make the work interactive, not in the sense of a viewer controlling an interface, but of participating in the production of meaning. Of course the idea grew, as ideas do, and my vague notion of an 'immersive environment' soon snowballed into a four room installation; a foyer area, a cinema, a backstage room and a 'green screen' room. The logic was to present the real and manipulated films with the context and apparatus of their manipulation. To foreground the idea of manipulation, to stimulate suspicion and to create critical viewers.

In the end the space became a rare example of actually looking the way I imagined it would. The twin elements of suspicion and environment wove themselves together into quite a dense installation that seemed to successfully blur the boundaries between original and manipulated, stage and set, simulation and real. But, a result of this success was that it was also really quite hard to navigate the work. I had intended for viewers to feel dislocated by the installation experience, to question the authenticity of the cultural production and thus to become critically engaged with the material of the archive. However, I have the suspicion, that whilst I managed to successfully dislocate the viewer, the critical engagement did not always follow as I had anticipated. I have the feeling that the piece was missing a key, not as in for a lock, but for a map. A means of deciphering the code, or at least a trigger to start the process of deciphering. But maybe that is the role that this text can play; a kind of map to the installation that was (and will be) and the story of the installation which explored films with strategies which were originally literary. It seems somehow apt that we return to the form of a book as a means to tell this tale...

Not in The Title_02_Installation Shot_2012_(c)Hopkins-4

download text as PDF