Ochuo’s Funeral

2011

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-1

Ochuo, From The Shantytown To The White Cube Geography Of A Global Encounter - Olivier Marcel

original publicationtranslated from French

From October 2012 to January 2013, the Austrian art center Kunsthaus Bregenz (KUB Arena) exhibited a work dedicated to a resident of the Kibera slum: “Ochuo’s Funeral”, by Kevin Irungu and Sam Hopkins. This work, whose ideological foundation is to articulate the anti-world of the African city (Houssay-Holzschuch 2006) to one of the high places of globalization, is exemplary of Western cultural cooperation in Africa, just as much as a figure of success. As such, it gives a particularly good account of the transnationalization of the field of contemporary art and the reciprocal interactions that it gives rise to. As its acronym and architecture indicate, the KUB Arena is representative of the “white cube ideology” (O’Doherty 1999). Dominant paradigm of contemporary museography, the white cube confines the work between immaculate walls and separates it from the geographical context in which it is born, even when its authors claim the “contextual” or “relational”(1) character of their work . Taking this artistic posture literally, this article follows the idea that the socio-spatial modalities of such a “global encounter” (White 2011) carry meaning, not only in the specific context of a work and a city, but also more broadly on the organization of the field – that of contemporary African art – in which they participate. Indeed, since the 1990s, the Kenyan artistic scene has been redefined in terms of the integration of an African segment into contemporary art institutions, in parallel with the opening of the country to capital from developmentalist foundations. which accompanies democratization policies (Marcel 2014).

How does a group of artists based in Kibera, one of the symbols of poverty in Africa, manage to share an artistic program with celebrities of the caliber of Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol? Beyond the simple description of a trajectory, this article aims to question the modalities of production and circulation of contemporary art and thus to better understand the pragmatic conditions of the participation of Africa to this field of activity today globalized but not less hierarchical. As the East African economic capital, Nairobi occupies a decisive position in this perspective, because it plays the role of a hub, conducive to a certain artistic excitement as well as to the structuring of a market. African metropolises are privileged interfaces between artists who take advantage of the legitimacy of local resources (the “capital of autochthony” according to Renahy [2010]), and intermediaries who benefit from superior control of mobility to the on an international scale (“mobility capital” according to Ceriani-Sebregondi [2007]). The duplicity of artists' careers resulting from this situation has led researchers to conceive another Bourdieusian variation, that of “transcultural capital” (Kiwan & Meinhof 2011). However, through the type of interactions they facilitate, these global encounters precisely challenge the inertia of compartmentalizations that a conception of resources by capitalization presupposes.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-1

The approach proposed here is to observe the deployment in space of the resources of capable and competent actors (Genard & Cantelli 2007), simultaneously located and mobile. It is a question of restoring the circulation of the work by letting oneself be guided by its movements. Based on a multi-sited methodology and interviews conducted with around ten actors, this investigation links Germany, Kenya and Austria and is based on a geographical reading of discourses and tactics of actors, that is to say by indexing their analysis on the places practiced and the spatial imaginations summoned. In this respect, the geographical approach, attentive to places and mobility, can contribute to the understanding of the new circulations and interdependencies that are being shaped by the globalization of art. The challenge is to overcome both media stories, which are often content with a blissful reading that overvalues the individuality and talent of marginal artists, and those of an economicist approach, which reduce artistic exchanges to the expansion of United States-European domination (such as Quemin [2002]). The article first traces the meetings which led artists from Kibera to exhibit on the shores of Lake Constance. This progression then allows us to question the effects of mobility on artists and their work.

Contemporary art meets Ochuo

The starting point of this meeting is a transcultural project between Germany and Kenya, in partnership with the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi, entitled Conversations in Silence. It presents itself as a reflection on commemorative practices as part of a five-month collaboration between four young European artists graduated from the Bauhaus University (Weimar, Germany) and three Kenyan artists met through the network of the German cultural center and Sam Hopkins, the artist who initiated the project. The Bauhaus University artist residency in Nairobi was structured around performances and installations at various sites in the city and resulted in a grand opening in February 2011 and public discussions in the exhibition hall of the Goethe-Institut. The works presented display an openly conceptual artistic language that is part of contemporary practices (2).

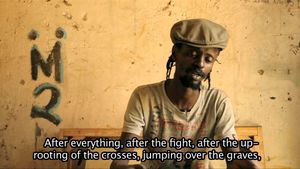

This article focuses more specifically on a piece resulting from this north-south exchange: a video installation on ordinary memory in a slum. The deliberately confusing synopsis of “Ochuo’s Funeral” invokes the figure of the ghetto underclass. A character with a tragicomic destiny, Ochuo earned his living in transport and informal trade in Kibera. After fighting in an obscure sausage theft case, the young man is imprisoned in Kamithi, and dies in his cell following ill-treatment. His only family, work colleagues from Kibera Drive, decide to collect money to give him a proper burial.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-2

After thirty days of matanga, community funeral rituals and festive fundraising, the money evaporates in alcohol and the group is forced to bribe the morgue keeper to avoid cremation. After a lap of honor to expose the body in Kibera, the convoy arrives not without confusion at its destination, but in the middle of the night and in pouring rain. After forcing the cemetery gate, the burial ended in drunkenness with a general fight with crosses torn off in the Langata cemetery (3). The Ochuo story, which began as a local news story, later became a folk tale told in local drinking establishments before being taken over by a collective of artists. The work is presented in the form of a video installation borrowing the codes of the police investigation to narrate this news item: it includes the video of a reconstruction of the funeral orchestrated by the artists (Sam Hopkins and Kevin Irungu) and a series of conflicting testimonies from witnesses to the event.

Sam Hopkins and his creative periphery

The initiator of the project, Sam Hopkins, was born in Italy to a British father and a Kenyan mother. Raised in Kenya, he studied art in Germany (at the Bauhaus University in Weimar), “social sculpture” in England and philosophy in Cuba. The recurring theme of his production is the beauty of popular knowledge. Through its multimedia projects, such as SlumTV, a production and distribution association audiovisual in the slum of Mathare, his objective is each time to give communities that he considers subordinate the technical means of self-representation, without seeking to dictate their content (4).

As a white artist, he is the first to reject the link between his trajectory and his work, describing it above all as “collaborative” and therefore “contextual”. Yet when looking at Hopkins' career geographically, it is telling that it was defined in Europe, and more specifically in an academic environment, as the cartogram of his spatial footprint reveals. Equally symptomatic is the absence of interactions with the network of African biennials and festivals in which Kenyan artists seem to have to distinguish themselves before leaving (Marcel 2012). At the time of this mapping, Kenya is its only African setting. In Hopkins' career, Kenya therefore figures as what could be described as a creative periphery, that is to say a space which provides access to raw material which must then be valorized by European authorities. The South would then be an artistic viaticum for the North, a logic of extraction which nuances its relational and collaborative approach.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-3

It is therefore hardly surprising that Hopkins relied largely on foreign centers (Goethe-Institut) or subsidized by Western foundations (Kuona Trust), which for him are anchor points in the city as much as possible relays in the world of contemporary art. Hopkins himself works mainly in the poor informal neighborhoods of the city (the slums of Mathare or Kibera), reproducing the pattern of occupation of the same developmental NGOs that he vilifies, which he tries to justify by personal affinities5, but is better explained by the spatial logic of his investment in Kenya and the notion of creative periphery.

When he talks about “Ochuo’s Funeral”, the artist’s references are mainly taken from the world of contemporary art. He cites, for example, Francis Alÿs, a Belgian artist renowned for his work on the materialization of rumors, and emphasizes his residence in Germany, where he said he was “impressed by the discovery of very advanced commemorative practices and the very conceptual approach to memory” (6). We can therefore say that the Conversation in Silence project was born intellectually in the North. From then on, his approach is geographically clear: “Bring these German commemorative practices to Kenyan terrain and rework them with local artists”7. From the original idea to the exhibition in Austria, the work results from a series of meetings and collaborations between individual actors, each with their own motivations, sincerities and expectations.

A circulation made of encounters

Hopkins' first collaboration was with the director of the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi, the organization that will host and finance (8) the project. Established immediately after independence in 1963, the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi built its legitimacy as a refuge for Kenyan intellectuals and artists. Elimo Njau and Joy Mboya, both founders of art centers presented as “indigenous” (9), recognize the assistance of these places during the Moi authoritarian regime, but criticize the presence deemed suspicious and problematic of European diplomacies on the country's artistic scenes (10) . And for good reason, in contrast to a dilapidated Kenyan cultural center, the Goethe-Institut tripled its budget in 2008 (11), consolidating its prominence in the staging of Kenyan art and its internationalization. In addition, easy access to the completely free programming of this cultural institute located in the historic and colonial center of the city makes it a privileged interface between the different social classes participating in the field of art.

Johannes Hossfeld, director of Goethe-Institut and originally from Cologne, is very familiar with conceptual arts and experimental media, like Sam Hopkins, since he started a doctorate in art history before joining cultural cooperation. It was under his leadership that the German cultural center became one of the main promoters of contemporary artistic practices with Kenyan artists (performances, installations, etc.). His arrival in Kenya coincides with a critical moment in the country's history: the 2007 presidential elections and the highly publicized deadly violence that followed.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-4

After this traumatic event, he felt invested with a responsibility for the processing of memory and initiated numerous projects in this area (12). Its policy reflects two desires: on the one hand that of local anchoring, with the favor given to projects which deal empirically with Nairobi and, on the other hand, a concern for relevance with the methods and standards of the field of contemporary art. Deploying, here again, an unambiguous geographical imagination, Hossfeld confided to me during a formal interview that his guiding principle is to “elevate local artists to the level of international scenes” and for this he admits “to work exclusively with artists connected or connectable to the international art circuit” (13). The project proposed by Sam Hopkins and the type of interactions it involves fulfill precisely these objectives.

The second meeting which made the work possible was that between the two initiators previously mentioned and the metropolitan intellectual sphere. This was done through local art centers and in a series of associated sociability places. Hopkins very quickly surrounded himself with influential artists, the photographer James Muriuki and the writer Charles Njoroge Matathia, without whom the project would have lost its legitimacy within the local art scene. These people come from wealthy classes and have all completed higher education in Kenya, in design, sociology and psychology. Although they also demonstrate an interest in identity and memory, their motivations are not the same as those of Hopkins or Hossfeld. It is first of all an intellectual curiosity about urban development and societal developments in Kenya that attracts them to the project. Matathia is a writer and activist affiliated with the Kwani urban literature movement. He was the screenwriter of the successful feature film Nairobi Half Life (2012) and wrote a blog on urban culture in Kenya (“A Kenyan Urban Narrative”). Muriuki is a photographer and exhibition curator who has distinguished himself on the international scene. He notably produced photographic series on urban heritage and served as exhibition curator in the former RaMoMa gallery, one of the important places for Kenyan contemporary art in the early 2000s, which gives him still some authority. Both share a quest for urban identity, which justifies their commitment to the project (14). More prosaically, these international collaborations are a way for them to expand their network and strengthen their local stature.

For this project, Hopkins and Hossfeld therefore established their local credibility by putting a foot in the Kenyan intellectual field. It is the legitimacy of the encounter between contemporary art and Ochuo that is at stake here. Indeed, the support of these notables defuses criticism of the exogenous nature of a project imposed on subordinate artists who would not have the luxury of refusing.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-5

In an honorary capacity, Matathia has also become exhibition curator (co-curator), a concession of part of the symbolic power and at the same time a guarantee of legitimacy in the Nairobian world (through the identity) and in the world of contemporary art (by status). This win-win arrangement is sealed by the co-writing of the project’s argument. Hopkins and Matathia together establish the conceptual, historical and political framework which is submitted to the different artists involved. This argument emphasizes “memories and forms of commemoration in different sections of Kenyan society” and “the possibility of investigating a collective memory – forging one if necessary – and developing commemorative works” (15). The objective is to promote a memorial narrative against state heritage16, this great absence from the project whose rejection is unifying17. Published on an internet forum for Kenyan literature (“Concerned Kenyan Writers”), this draft and the theme of memory are fully consistent with the concerns of the Kenyan artistic intelligentsia. For Gor Soudan, initiator of a circle of East African artistic critics (Footnotes East Africa), memory is a very current issue which “challenges the way we define ourselves, particularly in this urban context” which has become an “illusion”18 for its temporary users. For him, memory gives meaning to the urban experience. Thus, the initial artistic program, developed by Hopkins and endorsed by Hossfeld, was co-opted by Kenyan intellectuals and artists familiar with metropolitan cultural institutions and their functioning.

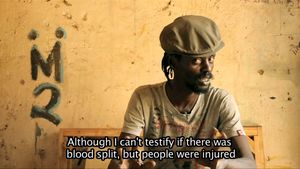

Final meeting allowing the creation of the work: the negotiation of this cultural and artistic program with a collective of Kibera slum artists: the Maasai Mbili. Sam Hopkins has been attending this collective since 2005 and has collaborated with it on several of its projects (19). These collaborations allowed him to be identified as a legitimate actor in Kenyan art (20). His mastery of Kiswahili and Sheng, a protean urban dialect between English, Swahili and community languages, makes him a trusted interlocutor for these artists. In addition, its international aura allows it to be a broker of choice between slum and artistic institutions in the city and beyond. Kevin Irungu, young member of the collective, will be co-author of the work “Ochuo’s Funeral”. He has not followed any formal artistic training and does not frequent the social spaces or discussion forums of the previous group. In short, he did not benefit from the same “artistic socialization” (Depres 2014). He joined Maasai Mbili in 2004 after dropping out of secondary school and then began craft painting with local businesses (sign painting). ), founding activity of the collective. He describes himself as a “person on the ground” who “knows local stories” (21).

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-6

Here again, the motivations for joining the project differ. Although very attached to the content of the work, the notion of memory is almost absent from his speech. When I asked him the question, he replied that “it is obvious that Kenyan history was written by the powerful” (22). What interests him more is the history of “the people below”. Rather than the conceptual language on memory, it evokes above all its “community”, its “culture” and the possibility of making this community an actor in identity processes, which legitimizes its commitment to the project.

Quite subtly, Irungu does not seem to be fooled by the exploitation to which he may be subject. When I ask him the story of his encounter with contemporary art, Irungu goes back to the foundations of the collective. “Maasai Mbili” means “two Maasai” in Swahili, the pastoralist ethno-linguistic group that has become the country’s tourist icon. Irungu recalls that the name of the group comes from the cross-dressing of two founding artists, Otieno Kota and Otieno Gomba (neither of whom is Maasai), in order to draw attention to them. Throughout the collaborations, the group was exposed to a variety of artistic languages which opened up unsuspected horizons. Beyond the benefits in kind that it can draw from this experience (23), this group uses its capital of autochthony in tactics of accomplishment which rather suggest reciprocal instrumentalization.

The beginnings of this artistic project are consistent with the definition given by the anthropologist Bob White (2011: 6) of the “global encounter”, that is to say “situations in which individuals from radically different backgrounds and perspectives meet and interact together. with each other on the basis of limited knowledge regarding the values, resources and intentions of the other” (24). On the other hand, these meetings are part of the logic of actors where each expresses a clearly defined status. We thus distinguish between prescribers, brokers, or moral or intellectual guarantors. These roles are not just sociological but also geographical, to the extent that they correspond to positions, refer to places and represent scales of action. Through the interviews of each of the actors involved, it is remarkable that the mobility that such a project allows is expressed according to different geographical references: bringing the "local" to the "international" for some, circulating " national practices” and “reinventing the national narrative” for others, or even making “people from below” speak: a variety of geographical imaginaries which cover different ways of considering mobility.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-7

The spatial imaginations of Ochuo’s reincarnations

The deployment of the work confronts a diversity of socio-spatial configurations. Ochuo, a figure of the Nairobi sub-proletariat, was, so to speak, reincarnated in several distinct events and exhibition venues: the reconstitution by Sam Hopkins and the artists of Maasai Mbili, in situ performance; the exhibition in downtown Nairobi, a moment of crystallization of different socio-spatial positions; and finally export to a contemporary art museum in Austria. Each of these places activates distinct networks and gives rise to sometimes opposing readings of the work.

A triple set of scales

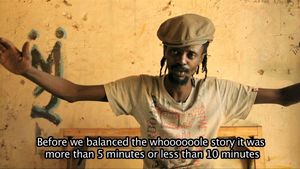

When Kevin Irungu guided Hopkins into the belly of Kibera, Ochuo existed only as an urban legend circulating in the neighborhood's informal drinking establishments (busaa clubs). It was in these bars that the two artists unearthed the story. What follows is a series of breaks in scale that go hand in hand with the mobility of the work. The father The first reincarnation is that of in situ reconstitution, a performative gesture aimed at transforming an urban legend into a work of art. The network mobilized is that of proximity and neighborhood. Indeed, Hopkins and Irungu appeal to people who participated in the real funeral, seeking to generate popular enthusiasm. A procession of slum residents returns to the Langata cemetery and reproduces the general brawl, this time in front of Hopkins' camera.

The second reincarnation, that of the Metropolitan Gallery, was accompanied by presentations and public debates. The exhibition lasts three weeks. It is a public success with more than 150 signatures in the guestbook: there are residents of Kibera, but above all expatriates accustomed to the cultural life of Nairobi. This relocation of Ochuo nevertheless gives rise to bitter discussions and controversies. As soon as the opening, one of the exhibition curators, Charles Matathia, slammed the door on the project following a disagreement “on the ethics and content” of the final exhibition, denouncing the imbalance of the exchange (25). He said he was particularly shocked by the drunkenness and the desecration “orchestrated” by the image takers and no longer wanted his name to be associated with the exhibition (26). For him, this subject deserved to be treated with more respect towards the Kenyan context and required psychological precautions to prevent the subconscious trauma that this macabre reconstruction could cause. This outraged criticism is then shared by part of the intelligentsia who see in the work another avatar of the postcolonial situation and a new glorification of the slum carried by foreign artists and institutions (27).

For their part, Hopkins and Hossfeld were fascinated by the turn of events, gravely observing the impact of the initiative (28). It is precisely these controversies that will give rise to Ochuo's third reincarnation, this time in a contemporary art museum in Austria.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-8

The curator of the KUB Arena, Eva Birkenstock, is a personal acquaintance of Hopkins who he met during his studies in Germany. She visited Kenya in 2012, first as a tourist destination, then as a study site. We will note here all the ambiguity of the relationships that can be established between vacationing curators and artists, between the search for exoticism and adherence to contemporary practices. For the Austrian contemporary art museum, the geographical opening “to the South” can be seen as a mark of avant-garde and facilitate future collaborations with artists from emerging markets, even if bringing in the Maasai Mbili was not not immediately profitable. In addition, for Birkenstock, collaborations with cultural cooperation institutions represent a means of expanding its network and opening up new professional opportunities (29). During his visit to Nairobi, Hossfeld and Hopkins were key contacts and it was by following their recommendations that Birkenstock took the pulse of the city. She visits the Goethe-Institut, the Kuona Trust, the GoDown Arts Centre, the One Off Contemporary Art Gallery, the Maasai Mbili Centre. This circuit brought her back in the footsteps of Ochuo and his controversies.

The sociologist Nathalie Heinich (1998) theorized the functioning of contemporary art as a three-way game between the artist, the institution and the public: for her, artists' experiments now aim for controversy with the public and force institutions to increase their permissiveness. Institutional integration encourages ever more daring transgressions in the eyes of insiders, in turn triggering ever more violent reactions from neophytes. It is interesting to note that in this north-south exchange there is a transfer of the mode of operation of Western artistic modernity. Indeed, the controversy surrounding Ochuo gave value to the work within the Austrian institution, which contributed to its international mobility (30). Tellingly, Eva Birkenstock asked me to send her the proceedings of a conference in which I took stock of the Ochuo controversy (Marcel 2012). She justified this request by the fact that this article could be used by KUB Arena mediators in preparing guided tours31. This clearly demonstrates the added value of the Nairobi controversy in the eyes of this institution.

The triple play of sociological instances identified by Nathalie Heinich responds to the symbolic progression of crossing geographical scales which can be defined as social constructions of spatial imaginations of globalization (Marston et al. 2007). The geographical reading of the mobility of “Ochuo’s Funeral” shows these global encounters as places of confrontation of scales, knowledge and practices that they represent. On the one hand, we observe that the actors seize the “local”, the “urban” or the “international”, and seek to become their representatives, even their guardians.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-9

This allows them to be associated with the formation of a value chain of which the KUB Arena is the culmination, a place where the international dimension of the artist is enshrined. On the other hand, this artistic project brings together representatives of different scales of action. The latter then serve as a resource in the play of actors and explain the logic of alliance and reciprocal instrumentalization. We can then wonder how the circulation in this play of scales affects the very meaning of the work.

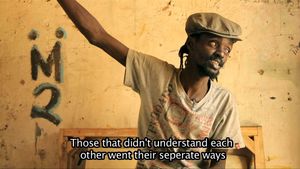

Mobility and translation

During my investigation, I asked the different actors “Who was Ochuo?” » and “What is the meaning of his story?” ". Kevin Irungu, the Maasai Mbili artist, above all wanted Ochuo’s story to be “funny, to make people laugh” (32). This perception contrasts with that of Hopkins. Although he does not deny the dark humor in the story, he prefers to speak of an “enigmatic”, “tragic”, “jubilant”, “surreal”, “touching” and “melancholic” event (33). The Kibera artist is aware of this gap in perception and confirms to me that Hopkins was there more for memory than for humor. When I interviewed people there, the experience was mainly experienced as a humorous parody with an expiatory dimension of self-deprecation. It would therefore be simplistic to see only a posture of extroversion since the local residents found themselves in the content: "In Kibera, everyone loved it, it's normal, it's our culture" explains Irungu, adding no without pride having “created a monument for Ochuo” (34). From the exhibition in the Goethe-Institut gallery, commentators saw something more generic. The artist Gor Soudan judges that it is an evocation of “what people cling to”, a metaphysical piece about the “African city dweller” (35). Hopkins develops another reading. For him, it is not really a work about Kibera, nor even about the individual Ochuo, but rather a “ghetto fable”, “a monument to a socio-political context which made it possible to happen” (36). The translation reaches a new level of abstraction when it is approached by Eva Birkenstock's team in Austria, where the work then serves as "a reference to all the relationships, temporalities and spaces that constitute the city present and past” (37).

The story of Ochuo refers to practices and representations of death that are culturally marked. This burial goes in particular against the dominant funeral narrative of important men, the big men, where the place of burial is an extremely sensitive fact and where solemnity is required (Cohen & Odhiambo 1992). In fact, being buried in Nairobi is already a sign of a certain moral decline in the Kenyan collective imagination. Even in popular categories, families do everything to repatriate the bodies of the deceased to their province.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-10

Until recently, Nairobi had the particularity of being a “capital without cemeteries” (Droz & Maupeu 2003) – or almost, that of Langata being a remarkable exception. Thus, the Maasai Mbili defend themselves from accusations of exploitation by recalling that Matathia, the harshest critic, is not Luo and did not grow up in a slum. For Irungu, fights during a funeral are part of the expected (38). Gor Soudan, who grew up in the country's western Nyanza province, confirms that the Luo ethnolinguistic group has specific burial practices to chase away spirits. For him, the people of Kibera are above all Luo who adapt their culture to the urban environment (39). Successive reincarnations gradually blur this anthropological complexity of in situ performance, in favor of a narrative that tends towards the conceptual and all-encompassing. According to Sam Hopkins, “contextual” works are intended to exist independently of the context (40), which justifies for him to do an exhibition on Nairobi in Austria. However, the study of the circulation of this work reveals an almost literary translation of the script, as its mobility breaks geographically. Even if the formal content of the work and its staging in the hall of the Goethe-Institut and the KUB Arena are almost identical (41), there is an increase in generality which seems to respond to each change of location: sometimes a humorous parody for the participants, sometimes an insulting cliché for the city's residents, or even an allegorical and metaphysical work for the people who will promote the work in Europe. The point here is not to make a value judgment on these opinions but rather to note that the geography of art affects the meaning and the very nature of the work.

This case study questions the conditions and meaning of travel as well as the future of the actors involved in the field of contemporary African art. By retracing the interpersonal encounters of the genesis and the development of this artistic project, it is possible to better understand the way in which artists' mobility is negotiated in Nairobi. Art historian Sidney Kasfir restricts the international mobility of contemporary African art to a privileged class. According to her, “these stays abroad are only possible for a limited number of people who meet the following criteria: speak the language of the host country, have recognized diplomas, have the necessary funds for the trip and benefit from a network of influential contacts on site” (Kasfir 2000: 190). However, the institutional emergence in Nairobi, although it does not radically blur these socio-economic determinants, complicates them by pushing an entire generation of artists who do not meet these prescriptions towards an international horizon.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-11

The arrangement of such a transcultural project, typical of artistic exchange in the era of globalization, highlights that artistic production in Nairobi arises from a game where socio-spatial hierarchies are subtly deployed. Indeed, upstream of the project as well as in the extension of its mobilities, Nairobi is constantly referred to the “local” in the structuring of globalized art. Likewise, the interactions where the ideological, aesthetic and curatorial lines of the project are affirmed bring the Kibera artist into a game where he seems to gradually lose his grip. This study nevertheless invites us to think of global encounters in a certain fluidity of socio-spatial relationships and to think of artists as "smugglers of borders and otherness", individuals "who tinker, precisely from their circulatory experiences, mixed identities between near and far worlds” (Missaoui 2008: 186). What will Kevin Irungu remember from his stay in Austria and the meetings he will have there? How will this experience transform the mastery of his own mobility and the way in which he views the field of art? Following the exhibition of “Ochuo’s Funeral”, Irungu participated in the exhibition Hysterical Injustices, organized in the Kuona Trust art center (September 2011). Confirming the stylistic break that accompanied his mobility, he then left painting, his initial medium, aside to embark on an interactive and multimedia installation. This change in artistic language reflects as much a desire for mobility as it translates the injunctions of the new power relations in which contemporary art in Africa is articulated.

Ochuo's Funeral_01_Production Still_2011_(c)Hopkins/Stero-12

--

- Or, according to N. BOURRIAUD (1998: 117), a “set of artistic practices which take human relations and their social context as their theoretical and practical starting point, rather than an autonomous and private space”.

- There is a reinforced concrete pillar built in the heart of Kibera (Monument to the future, by Dusica Drazic), an interactive reflection on public space and memorial practices (Celebrating Hilton Square by Irene Izquierdo), or even photographs piles of potatoes against a background of Nairobian skyscrapers, complemented by a film praising the skills of street vendors (Kenyan pyramids by James Muriuki and Karolina Freino).

- The Langata cemetery, in the southwest of the city, is one of the few cemeteries in use in Nairobi. It is divided into two parts. The second, dedicated to the most modest, experiences a sustained turnover: each square of land is rented for six months, after which the coffin and the cross are dislodged.

- In his exhibition Sketches, at the Goethe-Institut in Nairobi in 2010, one of the works presented a patchwork of real and imaginary logos of NGOs working in Kenya, a way for him to raise the absurdity of certain developmentalist approaches in Kenya . He thus stood as a critic of the compromising relationship between development NGOs and cultural production.

- Interview with Sam Hopkins, Chai House, Nairobi, August 2011.

- “There was an elaborate discourse about commemorative practices and I was

impressed by a really advanced conceptual approach to memory” (ibid.).

- “I wanted to take this legacy of German commemorative practices and work it with Kenyan artists” (ibid.).

- Funding was shared between Bauhaus University and the Goethe-Institut.

- Elimo Njau and Joy Mboya are respectively the founders of the Paa ya Paa art center in 1965 and the GoDown Arts Center in 2003, two figures and milestones essentials of the history of Kenyan art.

- The 1980s in particular were a dark period for artistic creation Kenyan. Censorship and political repression lead many to silence or exile, like the famous playwright Ngugi wa Thiong’o. The Goethe-Institut and the French Cultural Center then constitute refuges of freedom of expression where intellectuals and artists meet. On the other hand, since the political change and the coming to power of Mwai Kibaki in 2003, this justification no longer applies. However, in 2010, foreign cultural centers alone represented almost a third of the artistic events published on the NairobiNow cultural calendar.

- This explains why during my fieldwork, Johannes Hossfeld was a key figure for many Nairobian artists.

- He was notably one of the initiators of the Re-membering Kenya conference in 2008, the proceedings of which he published (MUNGAI & GONA 2010).

- “We want to bring the local artists up with the international art scene”; “We work exclusively with artists who are connected or connectable with the international art circuit” (interview with Johannes Hossfeld, Goethe-Institut, June 2010).

- The years following the post-electoral violence of 2007-2008 were marked by the development of new forms of identification, particularly among young urban dwellers, which can be described as post-ethnic. In Nairobi, this was manifested by the appearance of cultural and artistic cybercafes focused on the cohesion of civil society (Pawa254, iHub, The Nest), which emerged with the support of international cooperation and of developmental foundations.

- “Forms which commemoration and remembering take within different sections of Kenyan society” and “the extent to which artists can investigate a collective memory—forge one if needed—and develop commemorative artworks”: S. Hopkins and N. Matathia, Conversations in Silence, draft published on the literary forum “Concerned Kenyan Writers”, 2010.

- “Celebrate”, “speak to” or “invent” memorial narratives for Kenya, outside of the “government reports” and the “official record” (ibid.).

- When the Bauhaus University artists arrived, Hopkins organized a group tour of the Nyayo Monument, the building honoring former President Daniel arap Moi, in the city center. The project’s argument harshly judges these state policies: “childish and two dimensional”.

- “It challenges the way you define yourself, especially in the urban setting. We come to look for money and livelihood but every Christmas and Easter, we go back home. The urban area becomes like a sort of illusion” (interview with Gor Soudan, in his studio at Kuona Trust, September 2011).

- For example, he produced the portraits of Pets of Kibera (2010) or the curatorial project on African megacities Afropolis (2010), in which he associated the Kibera collective.

- It will be noted that on the annual reports of Kuona Trust, he was given the “UK” identity in the early 2000s and was then assimilated to Kenyan artists.

- A “ground person” who “knows local stories” (interview with Kevin Irungu at the Maasai Mbili studio, August 2011).

- Ibid.

- The Maasai Mbili speak of “art materials”, a joke to evoke the alcoholic per diem substitute they demand in return for their participation.

- “The notion of “global encounters” refers to situations in which individuals from radically different traditions or worldviews come into contact and interact with one another based on limited information about one another’s values, resources, and intentions. »

- “We had a rupture with Mr. Hopkins over ethics and content”, specifies a public press release from C. Matathia, February 2011.

- “You can’t just give Maasai Mbili alcohol and miraa and ask them to do any old stupid thing because they won’t refuse—it’s just wrong”; “The word taboo actually means something locally”; “This is only showing their nakedness” (interview with Charles Matathia, Storymoja Festival, September 2011).

- “We are forcing that kind of language on M2”; “The ghetto has become glorified. It’s a brand being sold to the world”; “It is making a memory of accepting to be poor” (interview with Gor Soudan, in his studio at Kuona Trust, September 2011).

- “We’ve probably elevated a criminal to some folk hero status” (interview with Sam Hopkins, Chai House, Nairobi, August 2011).

- In 2014, Eva Birkenstock was selected by the Goethe-Institut for a one-year residency in an exhibition space in Manhattan, a professional opportunity which is not unrelated to the reception of the Kenyan delegation, under the aegis of the Nairobi branch of the German cultural network.

- This international mobility takes place in a dematerialized format since the coffin and the crosses – the only material elements of the video installation – are reproduced on site.

- “As Sam told you, we are showing the work within an exhibition in Bregenz and would be very interested in reading your text, and if possible, would like to give it to the art mediators to prepare for their tours” (email communication with Eva Birkenstock, then curator of the KUB Arena, October 2012).

- “For me its humor [...] I want it to be funny, I want people to laugh” (interview with Kevin Irungu at the Maasai Mbili studio, August 2011).

- “Enigmatic”, “tragic”, “celebratory”, “surreal”, “touching”, “melancholic” (Sam Hopkins interview, Chai House, Nairobi, August 2011).

- “In Kibera, everyone loved it. It’s normal, it’s our culture”; “We created a monument on Ochuo” (interview Kevin Irungu at the Maasai Mbili studio, August 2011).

- “It’s a piece on African urban dwellers”, “what people are hanging on to” (interview with Gor Soudan, in his studio at Kuona Trust, September 2011).

- A “ghetto fable”, a “ghetto narrative”; “not really about him as an individual in this other layer he is existing in [...] it is not a monument to Ochuo but one for a social-political context that allows this to happen” (interview Sam Hopkins, Chai House, Nairobi, August 2011).

- “A picture of Nairobi with reference to the ensemble of relationships, temporalities, and spaces that constitute the city’s present and its history”, presentation of the exhibition Nairobi — A State of Mind by the KUB Arena.

- “If people don’t fight at your funeral, they will forget you forever. It’s normal here” (Kevin Irungu interview at the Maasai Mbili studio, August 2011). Irungu refers to the luo tero buru ceremony, literally “bringing to dust” in Dholuo, where deviant behavior such as drinking and hysteria are more or less accepted.

- “Luo funerals have these ceremonies for chasing the spirits away, and most people in Kibera are Luo”; “Ochuo’s friends did this in their own urban way” (interview with Gor Soudan, in his studio at Kuona Trust, September 2011).

- “Ideally, the work exists beyond the context” (Hopkins cited in HOSSFELD 2011: 12).

- The same architects responsible for the exhibition hall of the Goethe-Institut were also summoned to Austria in order to recompose the staging of the exhibition. They are Naeem Biviji and Bethan Rayner of Studio Propolis, based in Nairobi.