Once upon a Time

2013

Once Upon A Time_02_326 | 203 | 301 | 656_Still_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-5

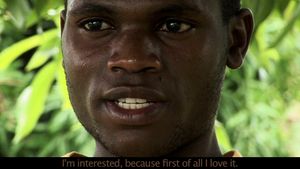

Chapter Two: the Abayudaya - Maggie Yates

Excerpt from 'Gather us Together as Jews From the Four Corners of the Earth: The Emergence and Endurance of the Abayudaya in Uganda.'

Locating the Abayudaya

The Abayudaya of Uganda are the only known Africans to have seemingly spontaneously converted to Judaism without external Jewish involvement or influence. In order to understand how and why this conversion occurred, it is crucial to discuss the historical circumstances that contributed to their conversion as well as the economic, political and social circumstances they currently navigate in order to maintain their Jewish observance. In this chapter I therefore, first outline a brief pre-colonial and colonial history of Uganda and then move to the Abayudaya’s historical development as a community. I have not attempted to triangulate all of the oral histories I collected from my informants in addition to the few histories published by scholars in order to write an objective history of the community. Instead, through this chapter, I attempt to present the Abayudaya’s understanding of their own history. In doing so, I invoke Liisa Malkki’s concept of a “mythico-history” in order to highlight the current significance of the Abayudaya’s constructed past (Malkki 1995). Once we have located the Abayudaya within Uganda’s pre-colonial and colonial history and identified the meaning of the community’s constructed history, we can begin to explore the factors that led the Abayudaya to a Jewish conversion.

The Nation: A Brief History of Uganda

Nestled in East Africa, Uganda is neighbored by The Democratic Republic of Congo to the west, Sudan to the north, Kenya to the east, and Rwanda and Tanzania to the South. Lake Victoria also constitutes most of the country’s southern border (Ofcansky 1996:3). The country is lush with tropical fauna due to its fertile land and ample rainfall. Uganda’s population of over 32 million consists of approximately 40 ethnic groups speaking over 30 languages that never considered themselves in pre-colonial times as single, unified nation (Ofcansky 1996:74). The history of these groups and the antecedents of the nation of Uganda date back to the fourth century BCE when hunter gatherers, agriculturalists and pastoralists, originating from West Africa migrated to the forests surrounding Lake Victoria, while inhabitants from northern Africa settled in the northern and eastern regions of the country (Ofcansky 1996:14).

As the population grew due to agricultural abundance, four kingdoms emerged. The Bunyoro-Kitara was the first kingdom to develop and was centered in West central Uganda, followed by the Buganda Kingdom in the south central region of the country, and later the Ankole Kingdom and the Kingdom of Toro (Ofcansky 1996:15). These kingdoms were often in conflict with one another, but the Buganda Kingdom was historically the most influential group (politically and militarily) in Uganda.

Once Upon A Time_02_326 | 203 | 301 | 656_Still_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-5

Although comprised of immigrants, the Baganda “developed a highly refined sense of its superiority, which caused a backlash among other peoples” (Ofcansky 1996:15). Due to strong resentment, the Baganda were forced to control their kingdom with military force. Following the arrival of the British in Uganda, the shared sense of resentment among other kingdoms for the Baganda intensified due to special privileges granted to the Baganda as an ally of the colonial power (Ofcansky 1996:15).

Although Muslim traders from the North arrived in the country in the 1830’s, thirty years before British forces entered the region, it was the European missionaries who began to alter the region’s internal structures (US Department of State 2010). Prior to European contact, each ethnic group had varying religious traditions. Most centered around a single supreme being, except for the Baganda who believe in multiple gods (Ofcansky 1996:74). Islam was introduced to the region through Muslim traders around the 1830’s. King Mutesa of the Buganda Kingdom actually converted to Islam in order to access the superior technology of Muslim traders, and he encouraged his subjects to convert as well (King, Kasozi, Oded 1973). In 1877 British missionaries from the Church Missionary Society arrived in the Buganda Kingdom, followed by French Roman Catholic Missionaries in 1879 (affiliated with the Society of Missionaries of Africa) (Ofcansky 1996:18). Initially, King Mutesa pitted the missionaries against each other in order to avoid the spread of their influence and the further intervention of foreign powers. But many European states were interested in the region, if not for religious motivations then due to speculation that the territory held the source of the River Nile. The British ultimately gained full control over the country in 1890 after Germany signed a treaty relinquishing control of Uganda to the British Government. Four years later, Britain officially declared Uganda a British Protectorate (Ofcansky 1996:19).

But the British lacked the military forces in Africa to expand their territory and enforce their rule, so they recruited Ugandan military leaders and their forces to aid the colonial conquests of surrounding groups. Semei Kakungulu, a Muganda (1) and a central figure in Uganda’s military history as well as in the Abayudaya's development, led several successful military campaigns, significantly extending British rule north and westward. In addition to military forces, the British also lacked trained administrative personnel in Uganda. As a solution, the British enforced a policy known as indirect rule in the colony. Colonial officials appointed Ugandan figureheads to collect taxes, maintain stability, and report back to the colonizers (Mamdani 1996:39). Positioned as British allies, the Baganda elites were the popular candidates to fulfill such administrative roles. The British “preserved Buganda’s traditional ruling hierarchy” and “gave Buganda special status enjoyed by no other kingdom” (Ofcansky 1996:22). Consequently, officials solidified Baganda traditions and political structures as the customary law of the colony, forcing different kingdoms with differing traditions to abide by Baganda custom.

Once Upon A Time_01_Production Still_Samson_2013_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-4

Ugandans were entwined with British interests. In fact, thousands of Ugandans served in the British forces during WWI and WWII. The return of these “approximately 55,000 ex-servicemen, many of whom possessed political and organizational skills” helped incite national discontent against the colonial regime (Ofcansky 1996:26). The exile of the Baganda King as a result of disagreements over policy changes with Uganda’s governor Andrew Cohen heightened the discontent of the nation’s most prominent constituency in Uganda (Ofcansky 1996:35). Yet compared to other African colonies, Uganda lacked a unified nationalist movement prior to independence (Ofcansky 1996:34).

Despite the absence of a nationalist movement, Uganda attained independence in 1962 under the leadership of Milton Obote and the United People’s Congress (UPC). Uganda continued to be plagued by division and instability following the country’s independence, though, and several leaders cycled in and out of political office as a result. Obote ruled as Uganda’s first president until 1971, when the tyrant Idi Amin usurped power and instituted a military dictatorship. Over the course of the next eight years Amin’s regime slaughtered an estimated 300,000 Ugandans and Asian Ugandan citizens, and terrorized and tortured thousands more. Following Amin’s fall from power, four different presidential administrations were installed over the next seven years, including a second term by Obote (Decalo 1998:115-186). In 1986, after years of ethnic and political violence that centered around a competition for power between the National Resistance Army (NRA) and the Ugandan National Liberation Front Army (UNLA), Yoweri Museveni and the NRA claimed control of the country (Ofcansky 1996:58).

Museveni remains in power today. In 1995, he ratified the constitution. Ten years later, he amended the document to extend the number of consecutive presidential terms permitted for an individual to serve (Musoke 2009). Museveni has made some improvements to the nation’s infrastructure and healthcare system, but his administration has been notorious in Uganda for corruption, hypocrisy and stagnancy. Despite the apparent governmental failures, however, Uganda continues to receive significant financial subsidies from the United States and other non-governmental organizations including the IMF and World Bank (US Department of State 2010). Although Uganda has vast natural resources including valuable minerals such as cobalt, its resources remain underexploited (Central Intelligence Agency 2010). Currently, an estimated 80% of the country’s labor force is involved in the agricultural sector and the GDP per capita as of 2008 was $1,300, thus reinforcing Uganda’s financial dependence on international donors (Central Intelligence Agency 2010). It is within this national history and current economic context that Abayudaya negotiate among local, national, and global forces.

Once Upon A Time_01_Production Still_Rachmann_2013_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-1

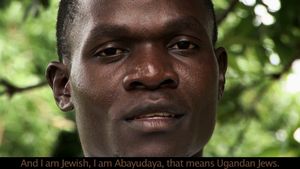

The People: A Current Overview of the Abayudaya

In the eastern region of Uganda near the border with Kenya, live the 1,050 members of the Abayudaya. The community, which consists of an amalgamation of several Ugandan ethnic groups is dispersed among eight villages that lie within 1 to 15 kilometers of each other and are primarily linked by dirt roads. Community members travel between villages or into Mbale, the nearest city, by foot or using public transportation, since they cannot afford the more expensive fare of motorcycle taxis.

With the exception of religious practices, the Abayudaya live similar lifestyles to their non-Jewish neighbors in the rural villages. The majority of the community, for instance, relies on subsistence farming and survives on less than a dollar a day. Families live in mud or concrete homes with thatched or tin roofs on small plots of land. Young children are responsible for hauling jerry cans full of water from the boreholes to their homes, since running water and electricity have not reached the majority of rural villages. Most of these children attend primary and secondary school, though not all, since some families cannot afford school fees and school supplies and need their children to help with agricultural pursuits. When children return home from school at the end of the day or during a holiday break, the young students accompany their mothers into the fields to tend to the crops, which include beans, bananas, plantains, and a variety of fruits. Men also farm, but women, as in all of Uganda, are a central if not the primary agricultural worker within the domestic unit. My Abayudayan host father explained to me that his wife is largely responsible for their gardens. Although he owns the land, she determines what crops to cultivate as well as when and where to plant and harvest them.

The community’s rural geographical “frontier” location and their isolation from basic technological developments (e.g. running water and electricity), are significant factors that shape the context in which the community reproduces and reinforces its religious and cultural practices (Kopytoff 1987; Malkki 1995:137). An African frontier location is defined by Igor Kopytoff as located “at the fringes of the numerous established African societies” (1987:3), and provides an “institutional vacuum” which allows communities like the Abayudaya to create or intensify the culture that they bring to this location (1987:14). The Abayudaya, however, interpret this “institutional vacuum” as “isolation” and associate it with hardship when re-telling their past. The community’s experienced isolation serves as a central motif within the constructed history of the community - or what Liisa Malkki refers to in her study of Hutu refugees as the “mythico-history” (Malkki 1995).

Once Upon A Time_01_Production Still_Jacob_2013_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-3

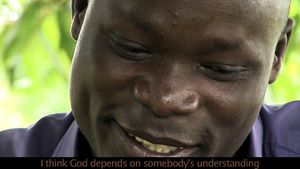

A mythico-history is a past constructed by the collective that emphasizes certain themes or events that provide the community with moral meaning. Malkki explains that the “mythico-history is misread if it is seen simply as a series of factual claims,” for the “facts” included are merely “building blocks for the construction of a grand moral-historical vision” (Malkki 1995:104). An appreciation for the Abayudaya’s understanding of their past is necessary to comprehend how they currently navigate transnational flows, which I discuss in following chapters. In addition to isolation, I suggest that the Abayudaya’s mythico-history also emphasizes themes of spirituality, persecution, and benevolent outsiders.

According to Abayudayan members today, their community initially broke off from a larger religious movement known as Malakite Christianity, in the early twentieth century (For further reading on Malakite Christianity see Hansard 1937; Lipschutz 1986)(2). Informants emphasized the purely religious justifications for the break, detailing how their leader Semei Kakungulu noticed contradictions between the Old and New Testament and was compelled to declare himself a Jew based on his convictions rooted in the Hebrew Bible. Community members today perpetuate the feeling of pride associated with Kakungulu’s declaration of the community’s Jewish values.

Following this declaration, Malakites shunned the break-off sect, exacerbating the Abayudaya’s geographic and spiritual separation. As the community followed Kakungulu to a frontier location, the Abayudaya were removed from the influence of other religious movements, colonialists, and the pressure to abide by strict customary law, thus allowing them to develop a unique religious practice. Informants, however, note this sense of isolation not as a crutch to the community’s survival, but as an obstacle to it instead. According to current leadership in the community, their isolation was exacerbated by their non- Jewish neighbors’ dislike for them and their later blatant discrimination and persecution against the Abayudaya during Idi Amin’s regime. In almost every interview I conducted, the Abayudaya discussed some form of experienced discrimination on the basis of their religious practice. Such an experience seemed to validate their religious identity, especially when the community explicitly drew parallels between their own persecution and the historical persecution of Jews. During the festival of Passover, for example, instead of discussing the persecution of the Israelites at the hands of the Egyptians that the holiday commemorates, the community shared stories of their own persecution under Idi Amin. By drawing comparisons between their own experience and Biblical precedents, the Abayudaya imply their spiritual worth and establish moral meaning within their mythico-history, not only for themselves, but also for foreign Jews interested and invested in the community.

Once Upon A Time_01_Production Still_Alex_2013_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-2

The Abayudaya’s first interactions with non-Ugandan Jews began with a single visitor from Jerusalem in the 1920s known in the community as “Joseph.” Several years later another foreign Jew involved with infrastructure construction in Uganda met the community. Then, in the 1990s the Abayudaya established significant contact with Western Jewry (3) and American Jewish institutions through their initial introduction to Kulanu, a New York-based, Jewish non-profit. Whenever speaking to me of foreign involvement in the community, community members consistently portrayed visitors as kind and knowledgeable and emphasized the benevolence of these outsiders. I was constantly aware, however, that the community viewed me as an outsider who held the potential to personally donate to the community, or return to my Jewish community in the United States and raise awareness and funds on their behalf. I am sure the Abayudaya were also well aware of this possibility as they shared with me their collective past. In her fieldwork, Malkki observed the ability of the Hutu’s mythico-history to provide meaning to “the socio-political present.” The Abayudaya’s constructed past serves the same function today as it informs their present actions and interactions with increasing numbers of outsiders (Malkki 1995:105). These actions are constantly being contextualized within their mythico-history, thus providing meaning and moral continuity (Malkki 1995:55).

In the past two decades, two United States based Jewish organizations, Kulanu and the Institute for Jewish and Community Research, have become deeply invested in all sectors of the community. In 2002, a delegation of American and Israeli rabbis traveled to Uganda to perform an official Conservative conversion for community members.(4) Although this conversion made the community “officially” Jewish according to the Conservative movement, the Abayudaya have identified as Jews since 1919, and since then have held worship services several times a week, observed the Jewish day of rest as well as kosher dietary restrictions. Israel, however, denies the legitimacy of the Abayudaya since the state only recognizes converts who undergo an Orthodox conversion (5) as eligible for Jewish entitlement to Israeli citizenship (See Lacey 2003). Israel’s refusal to acknowledge the community reinforces the Abayudaya’s emphasis on themes of spirituality and persecution during the telling their mythico-history.

Every history is subjective. Yet it is important to understand a community’s subjective interpretation of historical events in order to analyze their past and present activities as well as inter and intra-community relationships. Although the Abayudaya seem like an anomaly in a rural setting with a long history of Christian missionary work and Western oppression, Uganda’s historic context and the Abayudaya’s understanding of such a context, provides the starting point for understanding the emergence of this Jewish community.

Once Upon A Time_02_326 | 203 | 301 | 656_Still_(c)Hopkins/Odenbach-6

--

- A member of the Baganda ethnic group, singular.

- Note for future research: The British archives may contain more detailed information about the Malakite sect and perhaps the Abayudaya’s formation as well.

- It is important to note that although Jews from several Western countries including Great Britain and Canada visit the Abayudaya each year, my fieldwork revolves around the role American organizations and Israeli politics play in the Abayudaya’s reality. As a result, my discussion in the following chapters regarding the activities of “Western” or “international Jewry” in the community focuses primary on the roles of American and Israeli actors.

- The documentary Yearning to Belong records the Abayudaya’s 2002 conversion (Gonsher, Vinik 2007)

- Conservative and Orthodox conversions are similar processes. Both instruct the convert about how to live as a Jew and both require the convert to be immersed in a ritual bath in addition to making an agreement to live by the Jewish commandments. Male converts also undergo the ritual circumcision. An Orthodox conversion requires, however, that the members of the jury who determine the sincerity of the convert must be Orthodox Jews. Additionally the tradition requires that an Orthodox rabbi must oversee the conversion. Orthodox Rabbis do not recognize conversions done by Conservative or Reform rabbis (Jewish Virtual Library 2010).