A Topography of Loss

2021

Topography of Loss_01_Installation _Invisible Inventories RJM_2021_Documentation_(c)Diernberger

S/he Owes So Much That Even Her/his Eyelids Are Not Her/his Own. A Reflection - Sam Hopkins And Simon Rittmeier

original publicationSensing Agency and Charting Loss

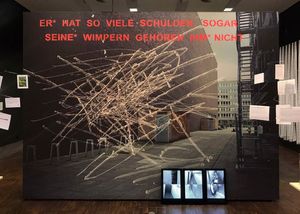

The work A Topography of Loss (2021) is a further inquiry into the agency of objects which we started to explore in our book project Letter to Lagat (Strzelecki Books, 2015). The book explores the site of an empty ethnographic and African art collection, and examines the question of what would be left when all the objects return home. We took a forensic approach to the museum and by envisaging it as a kind of crime scene we highlighted the power and agency of these objects and the multiple traces they left behind.1

When we first visited the storage facility of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in 2017, we immediately sensed a similar kind of agency. Deep underground, in a cavernous room of polished concrete floors and walls, gleaming under bright neon lights, we encountered the fully automated, five-metre high stainless storage system of the museum. And in each shelf, in sheets of foam cut to precisely 120x80cm, we found the objects of the collection. Approximately 65,000 objects lie in hand-cut, material-lined depressions.

To us, these negative spaces appeared to describe the loss of the objects from their communities of origin, both literally but also metaphorically. The immense number of depressions, each of which had been individually tailored to a particular object, seemed to speak of a museum approach which was both almost industrial in scale, yet was individually applied to unique artifacts. These negative spaces were not only bespoke prison cells, they also seemed to us like footprints that the objects had left behind.

We started to explore the particular depressions left by the eighty-three Kenyan objects that the museum has in its collection. As our ideas evolved, we began to imagine the depressions as hills and mountains—as a kind of landscape of loss. And then these hills became islands scattered in a vast ocean, a way for us to start to think through and represent the knowledge that was lost when these objects were taken from Kenya. How to navigate this vast territory? These ideas and imaginings led to the nautical chart which is at the centre of A Topography of Loss.

There are clear parallels between this nautical chart and the database of the International Inventories Programme; both are intentions to develop a form of archive, and have a speculative dimension. But where the database seeks to catalogue all Kenyan objects which are currently not in Kenya, the nautical chart offers a glimpse into a utopian future. Maybe one day, we will find only traces and emptiness as all the objects will have returned to their countries of origin.

Topography of Loss_01_Installation _Invisible Inventories RJM_2021_Documentation_(c)Diernberger

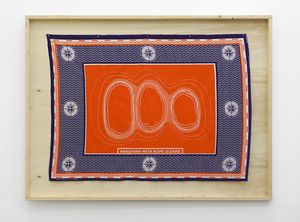

We wanted to develop an iteration of the A Topography of Loss series which could be distributed beyond museum-going audiences. A kanga seemed like an ideal form for this. It is a popular, indeed iconic Kenyan and East African garment which is printed with a central motif, a border design and a saying. Hence it is an article of clothing that you wear, and a medium with which you communicate (to your family, friend, neighbours, allies, rivals etc).

The design we developed with Thika Cloth Mills, a textile factory near Nairobi, consists of a central panel with three island-type motifs, below which there is a saying; “Anadaiwa hata kope si zake” (Kiswahili for “S/he owes so much that even her/his eyelids are not her/his own”). The motifs refer to three of the islands in our nautical chart of A Topography of Loss, which represent the hand-cut depressions in which three Kikonde belts are currently stored in the collection of the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne.

The Kikonde belts are from the Kamba community in Kenya and were wrongly labelled as “sword belts” when they came into the German museum at the beginning of the 20th century. Through researchers at the National Museums of Kenya (Jentrix Chochy, Juma Ondeng) we learned that in fact they have nothing to do with warfare. They are bracelets worn after Kithangona, a ritual performed either to thank or appease the spirits. There is no clear provenance available about their acquisition, or about how they came into the museum’s collection.

The Kanga as Medium, the Museum as Membrane

So far, we have shown A Topography of Loss three times, at the National Museums of Kenya (Nairobi), at the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum (Cologne) and the Weltkulturen Museum (Frankfurt am Main). But we remained inside the museum’s intellectual cosmos. The kanga was a first step out of this, an attempt to pierce through the museum’s membrane and find different ways where the ideas can travel. It’s an open, yet very physical manifestation of a thought.

By printing and distributing five hundred kangas, we are trying to free the idea to speak for itself, to be a kind of ‘agent’ which goes into the world and is not limited to our definitions in the same way it would be if it were only to be exhibited in a museum. And that means accepting, and even desiring, that our kangas might produce experiences which have nothing to do with our initial message.

Topography of Loss_01_The Kanga_Anadaiwa hata kope si zake_2022_(c)Hopkins/Rittmeier

The saying “S/he owes so much that even her/his eyelids are not her/his own” was intended as a statement towards German and Western museums and should not be understood as solely directed at one museum in particular. In fact, as we are currently citizens of Cologne, it is also directed towards ourselves, as we are also the “owners” of this collection; in the German federal system, museum collections are owned by the city in which they are located.

So, in a sense, the kanga’s saying speaks simultaneously to various parties: the museum in Cologne where the work was first conceived, us and citizens of Cologne, but also more generally to other city’s museums in Germany and the North. For us, it leads to a further question: What can a white artist from the North add to the debates around restitution? We have not lived the emotional impact, nor experienced the generational shockwaves of the aftermath of colonialism, something that The Nest Collective, our colleagues within the International Inventories Programme have spoken powerfully about.2 And we are part of the society who owns these collections. Next to our houses, collections which often have a violent history, are quietly hidden.

Artistic Research as a Common Good

We understand our way of working as a form of research, in that it is a sustained inquiry into a framed, specified area. But it is artistic research in which our research findings are often embodied and experienced by us personally in a very subjective way. So our art practice is both the vehicle of our research (the method) and the manifestation of that research (the form).

How do we share this type of subjective and embodied knowledge in a museum context, in which there is a clear mandate to communicate supposedly objectively to a broad array of audiences? And how to do this in a manner which does not compress, simplify or in the worst case, make our open and exploratory process redundant?

And what is the relationship of the museum to the capital which this research represents? Where does this knowledge reside? Does it somehow belong to us, the artists that developed this knowledge through their particular labour and research process? Is it a common good which was co-produced through a collective process and contributes to a broad discussion on restitution? Or does it just become absorbed and appropriated by the internal discourse of one particular institution?

Although we met plenty of inspiring individuals working in museums, we have become wary of the museum as an institution. So we would like to end by asking if there are other, non-institutional approaches to the museum. For example: Is it possible to work at museums rather than with museums? Is it legitimate for us as artists to wander into the museums (and the storage and archives) and then wander out again, without having to get entangled in the institution? Indeed are the conversations and negotiations with the institution really a necessary part of this work? — Because we are asking ourselves if we are actually interested in the museum itself. Maybe we just want to have the key.

Topography of Loss_01_Invisible Inventories exhibition, RJM_2021_Documentation_(c)Diernberger

--

- See Marian Nur Goni, « Agents in motion: how objects make people move. An interview with Sam Hopkins and Simon Rittmeier », Third Text Africa, n. 12, 2020, pp. 73-83 [online].

- See the project’s magazine (Iwalewabooks, Bayreuth/Johannesburg, 2021) and reader, What Can a Group of Citizens Do? Eight Nairobi-Driven Conversations on Restitution (Iwalewabooks, Bayreuth/Johannesburg), forthcoming.