Letter to Lagat

2015

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins/Rittmeier_(c)Wiedemann-6

Agents In Motion: How Objects Make People Move. An Interview With Sam Hopkins And Simon Rittmeier - Marian Nur Goni (1)

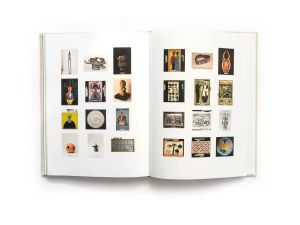

original publicationThis interview explores the research and artistic work leading to the artist book Letter to Lagat by Sam Hopkins and Simon Rittmeier which critically examines issues related to cultural flows and colonial violence, objects’ agency, presence and absence, through a reflection on traces, digital copies and 3D replicas.(2) Letter to Lagat employs a poetic and speculative approach to these questions: the starting point of the book is the sudden and total disappearance of the entire collection of objects from a museum in Southern Germany. But who is Lagat, to whom the artists address their book? And what do digital reproductions of objects do to the issue of the loss of objects? What do they embody effectively? In the course of the conversations, the artists speak honestly about how they tried to navigate these complex issues, not eluding difficult questions, doubts and shifting positions.

Since its publication, Letter to Lagat has acted as the foundational base for a new, ongoing, collective project — International Inventories Programme (2018/2021) — in which the two artists join forces with other artists (The Nest collective in Nairobi), researchers and museum professionals from the National Museums of Kenya in Nairobi, the Rautenstrauch-Joest Museum in Cologne and the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt/Main to gather and investigate a corpus of Kenyan cultural objects held in institutions outside the country.

#1 - ON THE AGENCY OF OBJECTS

‘The lines of desire (legible) in the corridor.’(3)

Marian Nur Goni: You employ this beautiful expression in the book: objects as ‘agents in motion’. I would like you to develop this idea because it is really at the core of your pro- ject. Also, in debates around restitution issues, objects are often apprehended from a hu- man perspective (the people who possess the objects, the people who lost the objects, etc.), while here you reversed the perspective. Where does this position come from, and where does it lead?

Sam Hopkins: We were interested in addressing this very confrontational debate around ownership which, in 2013 when we started to work on the project, was a different discursive field than it is today. There were still people justifying the ownership and possession of objects from the former African colonies through notions like the ‘universal museum’. Two impulses led us to the idea of approaching this argument from the perspective of the objects. On the one hand, there was a familiarity with Bruno Latour’s thinking that objects have a certain amount of agency which determines our interaction with them. This idea is an intrinsic element of his actor-network theory. On the other hand, there was the observation of the Iwalewahaus itself,(4) our forensic examination of its empty premises when it was being cleared out and all the objects were gone.(5)

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins/Rittmeier_(c)Wiedemann-6

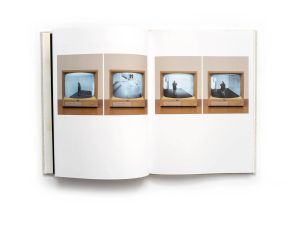

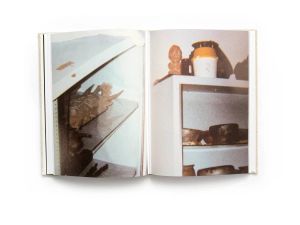

We were clearly confronted with traces that we then started to decipher. Some were very clear, like the marks of the shelving on the wall. We started to recognise the floors, which were very rich in material that spoke about the history of the building. We worked together with the photographer Hannes Wiedemann, who developed a way of taking photos of the floor and stitching them together to create an image which looked almost like an aerial landscape photograph. We saw clearly that the paths of the people walking through the corridor, through the rooms, were literally being shaped by the objects in those rooms. So, the source of our stance was two- fold: it came from this specific, theoretical framing of reality—the idea that objects have agency—and from our own engagement with the space itself.

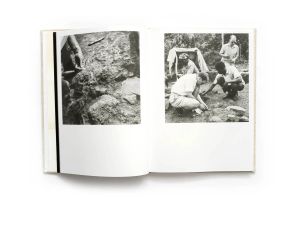

Simon Rittmeier: Yes, exactly. I would like to add that the motivation to think about objects as agents also came out of a frustration, namely that these objects couldn't move, and still cannot move, that they are somehow locked away in the storerooms. From this, we were investigating the movement of people around them. If you look, for example, at the first chapter of the book, you see photographs of archeologists digging in the ground. This, for me, is a very nice example of the idea of how an object makes people move. These archeologists think that they can find something. Sometimes they do, sometimes they don't. But in the end, there is always a huge amount of digging and work done. Also, in the case of the Iwalewahaus, we were suddenly confronted with the movement of objects themselves by the very fact they were moved from one building to another. So, in the process of the making the book, we were first standing in the archive with these objects unable to move and, all of a sudden, there was a movement of objects happening. This brought us to the idea of the vanishing archive.

#2 - ON A ʻCRIME SCENEʼ, ON ʻFORENSIC METHODSʼ

‘What information could we piece together about them? What stories lay hidden, waiting to be revealed?’

MNG: It is interesting that you speak about the archaeologists, Simon, precisely because I wanted to evoke the idea of ‘characters’ in the book. Weren’t you somehow playing the archaeologists in the rooms of the Iwalewahaus? Over the pages, we also have a sense of you being detectives in a space that acts like a crime scene, while Sam just recalled the forensic methodology that you adopted in the book.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins/Rittmeier_(c)Beier/CBCIU-0

SH: I find the figure of the detective a very productive and powerful device. Framing something as a crime scene is a way to encourage viewers to look critically and curiously, in a way that interrogates the images and the narrative that you are laying out for them. So, on the one hand, it is a form that we employed. But on the other hand, working in a foren- sic, detective-like manner was also an artistic strategy, a way of examining and exploring the physical space we were in.

MNG: But evoking a ‘crime scene’ here is also evoking the violence which, in many cases, was the condition under which objects moved during the colonial period.

SH: Exactly. I have employed the detective story/crime scene trope before but, in this context, I think it actually really made sense because it is not just a device with which to en- gage the reader. It is a device which has a definite resonance with the actual content of the book: there is a clear argument for the fact that this is a crime scene; there are very legitimate claims for the fact that many of the objects which are being stored in institutions such as these are objects which were taken in criminal circumstances and conditions. But rather than state explicitly that these objects were taken unlawfully and need to be returned, we worked on a more allegorical level.

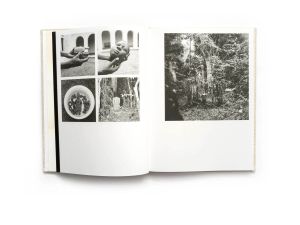

SR: We can also see the forensic methodology as a utopian idea: we were inventing a moment where a collection of African art and artifacts suddenly disappears. To quote Trinh T. Minh-ha, we didn't want to talk ‘about’ restitution, we wanted to speak ‘close by’.(6) Today, the whole debate has changed. By being allegorical, we chose not to concentrate on a du- al/binary question, ‘either/or’. We were looking at the objects from various angles and positions. Looking at their traces gave us the possibility to look into the future and to look at the past at the same time.

MNG: An important feature that is present in the book (but not that much stressed in cur- rent debates) is the link that you establish between the flow of objects during the colonial time and what is happening today with contemporary African art where artworks get mostly studied, exhibited, collected and conserved in the North.

SH: I'm glad you raised this point. Iwalewahaus primarily deals with modern and contemporary African art. It has a small ethnographic collection, which is part of the teaching collection. But they have not collected in the same way that Dahlem [the Berlin Ethnological Museum] or the British Museum or many other institutions have. But I do remember going to the collection — that was also part of the original idea behind the ‘Mashup the Archive’ project (7) — and seeing work by the painter Richard Onyango which I have never seen in Kenya.(8) This realisation was for me a very sad moment.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins/Rittmeier_(c)Wiedemann-3

#3 - ON A VANISHED COLLECTION. ON FORMS AND VOICES

‘Would their absence produce a vacuum here in this small German town?’

MNG: You both just recalled how the terms of the debate on restitution have dramatically changed since 2013 and you also evoked the real/imaginary vanished collection which you faced when the objects were moved from the former premises of the Iwalewahaus in Bayreuth to the new one. This is really interesting because the idea of the empty museum as a consequence of repatriation is still strongly expressed by those individuals who believe that these objects belong in the museums of the North and should remain there. In this argument, the empty museum is the expression of a fear, while you employ this metaphor in a very open way, which allows for the opening of many quietly-stated questions and speculations. Also, I just realised that these are often put on the bottom side of the page, written in small fonts. Actually, they act like footnotes. I was wondering then about the structure of the book: letter, footnotes...

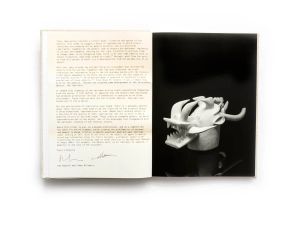

SH: I think we made three, possibly, four dummies of the book. We tried to narrate the whole story with no text, for example. At one point, we also had the idea for the book to read almost like a poem. Footnotes is a form that we both enjoy. Prior to making Letter to Lagat, I had read Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace: almost a quarter of the book is footnotes within the novel. Footnotes offered the possibility to give a sense of minutiae: textured, granular detail. Then, I think, Simon suggested the letter as a form to frame all of our questions. This also came about because we were interested in a clear perspective from the continent. And this is also central for the project [International Inventories Pro- gramme] that we do now.

At one point in our inquiries it became clear that we did not actually know what any muse- um professionals on the African continent thought about the topic of restitution and repatriation. We came across George Abungu's text which was a trigger for us to start thinking about the multiple perspectives of museum professionals in Africa that we, as people who are interested in this theme in Europe, had not heard about.(9) Hence, we had the idea to direct our questions to Kiprop Lagat who was an old acquaintance of mine, and at that time was working as a curator at the National Museums of Kenya.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_(c)Hopkins/Rittmeier-1

SR: Our book has a clear starting point: a collection in Southern Germany. If we try to imagine the void that is left behind when objects were stolen on the African continent, there are limitations to how we can understand this absence. So, if we speak about the objects’ histories, we have to start at the very end of the long trajectory of these objects — the rest can only be speculations. What is clear for me, as a white, European male who grew up in Europe, is that these objects mean something totally different than to a museum professional from Kenya. Therefore, we wrote to Dr. Lagat in the form of an extended letter — to start a conversation.

#4 - ON PITFALLS. ON WORKING AS ARTISTS WITHIN AN INSTITUTION

MNG: Retrospectively, and in the storm of the current debates about restitution issues, do you see shortcomings in the book?

SH: On the one hand, Letter to Lagat is like a parable, or an allegory—in a way, it stands for all collections. But, on the other hand, it can't stand for all collections. Every collection is unique and anchored in specific objects. We deal with a general condition: I think that allows us to do some things, but it does not allow us to do other things. We can speak allegorically but, by being general, some people might say that we are essentialising and simplifying ownership. There are many, complex ownership claims and histories of acquisition which cannot be dealt with as one general ‘thing’.

SR: I don't agree. I think that it is a parable that can be ‘transferred’ to other collections, ethnographic collections that host objects that date back to the colonial period. We were trying to speak about these kinds of collections that we find here in Europe.

MNG: But you did that at the Iwalewahaus, which has a quite different collecting history than other ‘ethnographic museums’ in Europe whose often dark histories you are pointing at in the book.

SR: You are right, this may also be the reason why they let us do this project. This is a very specific place, it is a small collection that is strongly connected to the history of one collector, Ulli Beier. They also already decided to critically engage with their collection, to do it with artists and scholars. This made it possible for us to speak more broadly about the whole issue. Ulf Vierke, the director of the Iwalewahaus, openly talked about the idea to burn elements of the collection as a symbolic act. This is just to evoke the very progressive state of mind in which we were working.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_(c)Hopkins/Rittmeier-2

SH: Ulf also had the idea to introduce a bot [a piece of code] into the digital archive, which would delete permanently, randomly, now and again, records from the archive. Bonaven- ture Soh Bejeng Ndikung mentioned this concept called apoptosis. It is a biological process that cells undergo in the body, some cells kill themselves in order for the body to survive. He suggested this concept as a way to think through archives because, by only letting things in and never letting things out, archives become really inhuman. Both of these proposals introduce a sort of mortality into the archive.

MNG: Did you have these kinds of conversations while conducting your work there?

SH: In the course of my work at the Iwalewahaus, I have had many conversations both with Ulf Vierke and Nadine Siegert about the archive. Simon is right: we were moving within a field in which it felt like we could do and share a lot. I never really felt an opposition between us and the institution. We did do a couple of things which we did explicitly ask permission for, but we really had very open discussions. Maybe we were not so conscious of it at the time, but I feel we had very special working conditions.

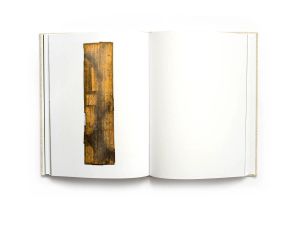

SR: There is also something else. The deeper you are granted insight into collections, the more of their fragility and weakness you get to see. In many collections there is no knowledge or only very basic information about the object's provenance. What you can find on the inventory cards is often only a region, or a ‘tribe’ and some presumed, generalised former use, like for example ‘bag of a ‘magic priest’. There is almost nothing about the cultural background, neither about the former owner, nor the religious or spiritual dimensions of the objects. In some of the German collections one can find entire shelves labeled as ‘UFO - Unidentifizierbare Fundobjekte’ [Unidentified Found Objects]. These are objects about whom nobody knows what they are, or how they ended up there. I argue that in their very substance, in their inherent concept, Western museums are not made for this information. This is why you will find numerous errors in the databases, and there is no- body around who could correct them. An intriguing idea was to do more research on how many objects disappeared from the Iwalewahaus collection during its life.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins-Rittmeier_(c)Fuentez-Gutierrez-5

I think it happens to every collection that objects disappear. Nobody knows where they end up or where they travel. We heard rumours that some archivists took objects to their private homes for their pleasure. Other works disappeared from one day to another. Were they stolen, and by whom? Did some former curator maybe restitute things as a ‘rebellious act’? And what about the personal connections that people in these institutions establish with objects they deal with on a daily basis? What remains once the objects are gone? Or, as we asked in the book: ‘Would it be a liberation for all concerned, the workers and the objects, like being liberated from an abusive relationship?’

#5 - ON REPLICAS

‘These replicas resemble ghosts, an eerie representation not of the objects, but of the knowledge that disappeared with the epistemic violence of the colonial project.’

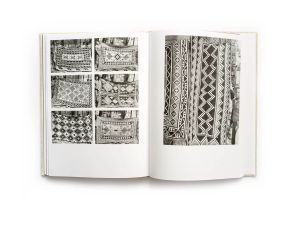

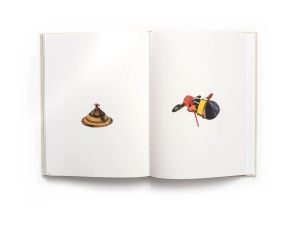

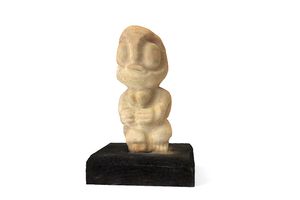

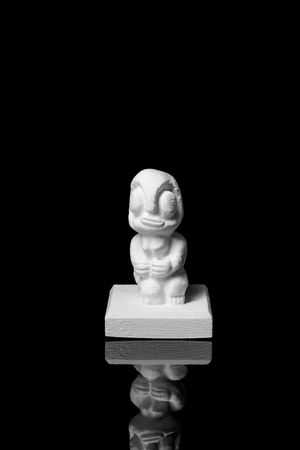

SR: I would like to add something about the pitfalls of the book. We avoided speaking about restitution, as one of the major ideas of the book was to look at the object’s trajectories and agencies. You could criticise the book in the sense that we were looking at the objects’ capacities. If you look at it from the perspective of the object being in Europe, it has traveled far because of its beauty and its strength, and the manpower that was once invest- ed in it. It has such a strong ‘DNA’ that today people are inspired and may want to produce replicas from it.

SH: If you look at the language of the letter, it's not impartial language. I think our position is very clear.

SR: Yes, but we actually proposed to Dr. Lagat if he would be interested in showing the replicas in Nairobi. Somehow, showing replicas there is like giving up on the idea of restitution.

SH: I think we need to be careful not to make this into a binary topic and conversation. If you read Letter to Lagat attentively, it is clear that the presence of the poorly produced plastic reproduction in Nairobi is asking for the object to be returned, without having to campaign in the traditional activist manner. For me, the strength of the book is that it makes its point in a much more subtle way.

SR: Yes. For us, it is a rhetorical question.

SH: This project was shown during an exhibition at the British Institute in Eastern Africa called Remains, waste and metonymy.(10) In the exhibition, we showed the replicas. It is more clear when you see the actual objects. Because in the book, the way we photographed the plastic objects, they seem very valuable, it is maybe difficult then to read that as a sort of ironic gesture.

MNG: Perhaps, if this was shown today, you would get other kinds of feedback.

Letter to Lagat_01_Book Image_2015_Hopkins/Rittmeier_(c)Wiedemann-4

SH: Definitely. Talking about pitfalls: Lagat in the book is a character. He does not have any agency. We wanted to position the book as a proposal to someone in the position like Lagat. And because of this stance, we needed a character like Lagat. But he did not choose that role, we developed this idea at quite a late stage in the project. We both felt that Lagat did not have enough of a voice, which is one of the reasons why we wanted to continue the project [which has now developed into International Inventories Programme].

#6 – ON WHO AND HOW TO TALK ABOUT THESE OBJECTS

SR: Indeed, it was a starting point for a conversation. It is like saying: “Look, this is where we are, this is how we feel about this issue”. But it is a complex one... I personally cannot really talk about the loss, of what has been lost through the removal of these objects from the African continent, because I am not from a community where objects were stolen, or forcibly removed, or sold in doubtful circumstances. So, how can I talk about these objects then?

SH: I think you put it very nicely, this is a central question to all these topics about cultural appropriation: what you can talk about, what you cannot talk about. I hope that you can qualify yourself to talk about things. I don't think that you are only qualified by the nature of where you were born, otherwise you would have a situation where all cultural production can only be autobiographical because you are only allowed to talk about what you know personally. This is a big topic at the moment. I find the idea of being allowed to speak about something really weird. At the same time, like Simon says, if you are Kenyan, regardless of whether those objects connect with your ethnicity, with your region, whether you have any idea of it, you've still grown up in a postcolonial country that is constantly dealing with loss on different levels. So, of course, you are going to have a different relationship with those objects. But I don't think that necessarily means that, as a white European man, you cannot talk about loss. You just talk about it differently. I would be wary to place values on those. This goes back to some of the discussions within the International Inventories Programme’s team: the idea that different people are entitled to talk about different things, that is something that I understand, but I find difficult.(11) Perhaps, with this book, we were also influenced by that... I don't know, maybe that was one of the reasons we made the book like this.

MNG: You mean that there were certain things that, somehow, you wouldn't allow yourself to talk about?

SH: No, what I mean is that, in the way that Letter to Lagat engages with the repatriation discourse, it is somehow the invisible thing which is not really talked about in the book. I personally think that makes it really interesting because it is never directly addressed. You can also see that as a result of the fact that our identities are not shaped by loss in the same way, as if we were black Africans living in Africa. So, yes, I think that shaped the whole approach.

--

- Excerpts from conversations held between June and November 2019.

- Sam Hopkins and Simon Rittmeier, Letter to Lagat, (Cologne: Strzelecki Books, 2015). Produced in conjunction with the Iwalewahaus Bayreuth, Germany.

- All quotes inserted at inception of sections are from Letter to Lagat.

- The research and art centre in Bayreuth where the two artists were working.

- The objects were moved to a new building.

- Trinh T. Minh-ha, Reassemblage (1982, 40 mins).

- For more information about the ‘Mashup the Archive’ project, curated by Sam Hopkins at the Iwalewahaus, see Sam Hopkins and Na- dine Siegert, Mashup the Archive (Berlin: Revolver Publishing, 2017).

- See Sam Hopkins, “Mashup Iwalewahaus: a conversation with Otieno Gomba and Kevo Stero,” Third Text Africa, vol. 4 (2015), 5.

- For Abungu’s response to the “Declaration on the importance and value of universal museums” signed by eighteen museums in the North, see George Abungu, “The Declaration: a contested issue,” ICOM News, no.1 (2004), http://archives.icom.museum/pdf/E_news2004/p4_2004-1.pdf

- Curated by Joost Fontein with Craig Halliday, see https://nairobinow.wordpress.com/2015/10/19/remains-waste-and-metonymy- oct-24-2015-british-institute-in-eastern-africa/.

- Members work in Kenya, Germany and France.

Unanchored, Destabilized: About Some Artists’ Books Using Photography - Fotota

download text as PDF